You can develop as an artist any way you wish. This post lays out a process of development that is generally, in one way or another, followed by successful artists. The steps are not necessarily linear, occurring one after another in a strict order, but they are usually present in the lives of writers and artists of all kinds. I’ll be curious to hear from you about your own development. Did it follow a direct path or was it roundabout? What steps were involved? How difficult was it? What did you learn from it?

My life of devotion to writing and studying the arts and the artist’s life—setting writing as a high priority in my life; thinking of it all the time; sacrificing for it—were shaped by these experiences:

In the third grade the teacher read to the class my theme in which I’d used poetic language (I’d written a simile), and I decided I would become a writer and write similes as often as I wanted the rest of my life.

In the third grade the teacher read to the class my theme in which I’d used poetic language (I’d written a simile), and I decided I would become a writer and write similes as often as I wanted the rest of my life.

At eight or nine I saw Laurence Olivier, the world’s greatest actor, in a movie on TV and decided that I wanted one day to be able to affect people the way his performance had affected me—he had made me gasp. Even as children we are able to recognize art at its highest and wish to know more about it and about artists who are such extraordinarily talented beings.

A major event for me in college involved another teacher, a well-known teacher of writing who one day read to the class a piece I’d written about my childhood. When she finished reading, she said, “A teacher waits her entire career for a student who can write like this.”

Very quickly after that, while still in college, I wrote a story that was published in a prestigious literary journal.

Then came the education, the writing jobs, the artistic friends, the teachers, the ambitions and goals, the teaching of others, and the hard work.

I entered the writer’s milieu—publishers, agents, best seller lists, book tours, foreign editions, television, radio, newspapers, magazines, reviews, public recognition—success.

Then I took off years reading, researching, and experimenting.

Next, while continuing to research especially on artists, I began writing blog posts.

At every turn there was positive feedback, reinforcement, and encouragement.

Steps

I’ve talked to many artists of all kinds and studied the lives of artists of every variety looking for patterns in their development: how did they become artists? In most instances the process of developing and perfecting an artist’s talent involves:

I’ve talked to many artists of all kinds and studied the lives of artists of every variety looking for patterns in their development: how did they become artists? In most instances the process of developing and perfecting an artist’s talent involves:

First signs of talent and interest: It may happen at any age–prodigies at three; painter Grandma Moses in her eighties. A child’s interest often follows an interest of a parent, and that parent often followed an interest of their parent. What is most amazing about young prodigies is that they are “pretuned”—they know the rules of their area of talent before being taught them. Few artists are prodigies, and in the overwhelming majority of cases later in life the artist who was not a prodigy–and often showed no particular talent in youth–surpasses the prodigy in achievements.

Some artists take to the art as a second career that may become a primary career, or they excel in both careers. Composer Charles Ives and poet Wallace Stevens were both also successful insurance executives. Award-winning American poet William Carlos Williams was a pediatrician. Prolific novelist Anthony Trollope was a British post office employee. Painter Henri Rousseau was a tax collector in Paris.

Interest aroused: There is almost always a moment in a talented person’s life when he/she became enamored of a particular art. There was a connection, a suitability, a symbiosis: the to-be-composer George Gershwin as a boy sitting on the curb outside his friend’s lower east side New York apartment and hearing him play the piano.

Trying it out/taking a stab: This often has a lasting effect, overcoming hesitation, shyness, reluctance, embarrassment, and fear.

Tentative commitment: “Okay, Mom, I’ll take lessons. I’ll see if I like it.”

A crystallizing experience: Often a moment occurs when the person’s existence seems to be organized and focused toward the art, a premonition that from that point forward the art will be prominent in his/her life.

A crystallizing experience: Often a moment occurs when the person’s existence seems to be organized and focused toward the art, a premonition that from that point forward the art will be prominent in his/her life.

Discovery of aptitude, Inclination, potential: Reinforcement comes from the outside–approval/ support/ applause/ a successful recital or performance in a play. You will not go terribly far in the art if your personality and skills are not synchronized, harmonized, and matched with those required to excel in the art.

Awakening of desire: “This is the right thing for me to do. I like this. I’m good at it. I want more of this. I will work at this.”

Establishment of “themes” important to the artist: Personal motifs begun earlier in life, often childhood, stay with the artist throughout life and are reflected again and again in everything the artist produces. These themes cannot be avoided; they are the artist’s “fingerprints.” Artists accumulate experiences, people, places, key episodes, and ideas which they will draw on the rest of their lives, endlessly recapitulating them in their work. These are the origins of their craft. Anyone who knows an artist’s work well is able to identify the artist’s recurring themes and subjects. His/her preoccupations are everywhere in the work.

Increased effort: Willingness to devote more energy to the art develops. What is often so impressive is how quickly some artists move from a first exposure to this level.

Self-confidence builds: The desire to succeed and the confidence that they can—along with skill and resilience—bring artists success. Those who are sure of themselves intensify their efforts when they don’t reach their goal and persist until they reach it.

Jelling: Everything starts to come together–ambitions, skills, progress, and success.

Deepening of desire: Stronger feelings toward the art increase; ambitions are raised.

Instruction, learning, knowledge, talent development: The specialized knowledge you accumulate through practicing your craft and receiving instruction, including self-instruction, is the most important factor in reaching exceptionally high levels of skills, possibly of greater importance than talent. The excellent writer or artist has acquired more sheer knowledge of the art and how to create it than the less excellent writer or artist.

All artists are to some extent studious and have the ability to apply themselves and to learn quickly; they are teachable. The need is for effective teachers. A poor teacher is as harmful, or is more harmful, than no teacher; the student of a bad teacher acquires bad habits. Being a stellar student in school is certainly not a prerequisite for artists. However, specialized training in certain arts such as painting and composing is often crucial.

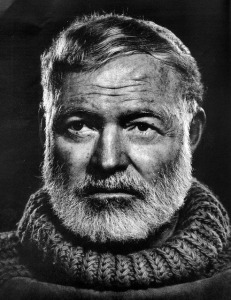

Mentoring, coaching, modeling, guiding: No artists—no human beings–reach their goals and achieve success without help. The older generation passes on knowledge, styles, and techniques to the younger who emulate the older. Mentoring often plays an inestimable role in artistic development, as the mentoring that Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound provided to a young Ernest Hemingway, helping to shape his revolutionary writing style, or that Sherwood Anderson gave William Faulkner, starting him off on his professional literary career, by asking his own publisher if they would publish his protégé’s first novel.

Close personal support, encouragement: Many benefit from connectedness to others such as writers’ or artists’ groups and at times in the relationship with one other person as lovers, husbands and wives, siblings, or close friends: Frederick Chopin/George Sand, Jackson Pollock/Lee Krasner, Jean Paul Sartre/Simone De Beauvoir, Henry Miller/Anais Nin, Virginia Woolf/Leonard Woolf, Salvador Dali/Gala, Thomas Wolfe/Maxwell Perkins, George Gershwin/Ira Gershwin. Most artists form a set of personal and professional relationships in the field that support them, find them opportunities, and rally them when they’re discouraged. The partner/mate of the artist often takes pressure off the artist, freeing him to focus on his work, as with novelist Joseph Conrad and his wife Jessie George.

Sustained deliberate practice: Months and years of work and improvements pass. The “ten year rule” (although it has notable exceptions) states that to progress from a novice to high expertise requires ten years of focused effort. That involves developing skills through intensive—often lonely–practice leading to competence, then to expertise, then excellence, then greatness. Even this process—tedious, boring, demanding—is a pleasure to the artist. Long periods of dogged hard work are nearly always the reason for superior artistic performance.

Sustained deliberate practice: Months and years of work and improvements pass. The “ten year rule” (although it has notable exceptions) states that to progress from a novice to high expertise requires ten years of focused effort. That involves developing skills through intensive—often lonely–practice leading to competence, then to expertise, then excellence, then greatness. Even this process—tedious, boring, demanding—is a pleasure to the artist. Long periods of dogged hard work are nearly always the reason for superior artistic performance.

More focused effort: Realizing that artistic success is feasible, the artist buckles down with stronger motivation, drive, persistence, perseverance. Expectations rise. Picasso said, “Everybody has the same energy potential. The average person wastes his in a dozen little ways. I bring more to bear in one thing only: my painting, and everything else is sacrificed to it…myself included.” Some ballet dancers with an eye to excellence practice until their feet bleed.

Experimentation: William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, and Eugene O’Neill began as poets, then switched to short stories and novels, or plays. Later in life short story master Anton Chekhov (the best there has ever been) began writing plays as well and discovered he could write masterpieces. A multi-talented man, Chekhov was also a practicing physician.

Narrowing down, specialization, development of a dominant style: As a result of experimentation and the clearer understanding of his strengths, weaknesses, and preferences, the artist defines himself more specifically: “I am a portrait painter.” “I paint skies.” A distinctive style (that develops over time) is the first sign of an artist’s high expertise. When I told that to the late composer/conductor Marvin Hamlisch, the composer of “The Way We Were,” and A Chorus Line, he asked, “Is that true?” and I said, “Marvin, you can’t write anything without my knowing it’s you.”

Breakthroughs: Often there are “years of silence” when the artist is working hard but has no tangible successes to show until the first successes which often then come in a flurry—novelists Jack London and William Saroyan received hundreds of rejections before their first success. Thereafter, everything they wrote was published.

Application, Working Harder: The taste of success creates a hunger for more success, which inspires more rigorous application and harder work.

Self-Education, self-determination: Every artist to one extent or another is an autodidact, a self-teacher. Some, like painter Vincent van Gogh and American poet Walt Whitman, were almost completely self-taught. Other famous painters studied with masters, but van Gogh and Henri Rousseau were exceptions. Writers are more likely than other artists to be self-taught. Most composers are taught by masters, and must have high potential to even be accepted as a student by the master. But classical composers Russian Alexander Borodin (also a chemist and physician) and Englishman Edward Elgar were essentially self-taught.

Settling on a Working Philosophy, Work Habits/ Tempo: Everyone working at an art develops his or her own work pace and philosophy of working. Van Gogh always painted at high pressure and at a feverish pitch, gathering up the colors as though with a shovel, throwing them on the canvas with rage, globs of paint covering the length of the paint brush and sticking to his fingers. He had no hesitations and no doubts. Cezanne didn’t understand van Gogh and told him, “Your methods lead to confusion. You don’t work in the manner of our ancestors.” American novelist Thomas Wolfe, a huge man with an equally huge capacity for work, wrote in a frenzy in clouds of cigarette smoke at lightning speed. Gustave Flaubert, on the other hand, worked meticulously, agonizing over every word in every sentence. Some film directors re-shoot a scene thirty times; others rarely more than once or twice.

Noticeable Improvement, refinement of skill, maturity: An evolution often occurs when the artist finds his “voice” as a result of long experience and reflection. Novelist Henry Miller: “It was at that point…that I really began to write… Immediately I heard my own voice…the fact that I was a separate, distinct, unique voice sustained me…My life itself became a work of art. I had found a voice. I was whole again.”

Greater reach, sudden growth spurts: At times, almost unaccountably, an artist experiences a leap in performance. The best example is Walt Whitman. In a short period he transformed himself from a below-average scribbler to America’s greatest poet.

Setbacks, obstacles, and Impediments: Artists often lead troubled, unconventional lives. Almost all go through fallow periods when success seems unattainable, but their recuperative powers seem inexhaustible and they work on, developing the resilience to rebound from setbacks. The incidence of addictions, mental illness (particularly bi-polar disorder), and suicide is considerably higher than that of the general population. Self-destructive American painter Jackson Pollack, American writer Ernest Hemingway, and too many poets to mention are examples. That, to me, makes artists even more remarkable, for often in spite of enormous personal problems that would debilitate most people, they still manage to produce tremendous volumes of artistic work of the highest quality. It is as though when they are focused on their craft all obstacles wither and disappear. Writer, poet, and essayist D.H. Lawrence wrote, “One sheds one’s sickness in books.”

Increased satisfaction, rewards, a way of life: Artists differ from one another in a variety of ways, but are unanimous in this way: they all love what they do. Their art provides a source of challenges, fulfillments, and opportunities for self-exploration and self-expression. The artist experiences the intrinsic satisfaction of continuous enjoyment from the art and the extrinsic benefits of success—particularly respect and praise—even adoration–and material rewards.

Increased satisfaction, rewards, a way of life: Artists differ from one another in a variety of ways, but are unanimous in this way: they all love what they do. Their art provides a source of challenges, fulfillments, and opportunities for self-exploration and self-expression. The artist experiences the intrinsic satisfaction of continuous enjoyment from the art and the extrinsic benefits of success—particularly respect and praise—even adoration–and material rewards.

You want to continue to make regular use of your principal artistic strengths–your main aptitudes, talents, gifts, personal qualities, and capabilities, to do so freely, without inhibition, without conflicts, and without being interfered with, and to be in a position to say every day, “Now, at this moment, I’m doing what I do especially well. I love it. It makes me happy.” Once you know you’re moving in the right artistic direction and feel strongly about it you fly through your days aflame with energy and determination. To become clear as to what your intended destiny is and to say to it, “I devote myself to you” is to feel an unstoppable drive toward its due fulfillment and to spring to life.

One after another, you overcome obstacles that are conspiring to keep you from your intended destiny, and now you are an artist.

© 2015 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

www.mentorcoach.com/rogershttp://www.mentorcoach.com/positive-psychology-coaching/interviews/interview-david-j-rogers/

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fighting-to-win-samurai-techniques-for-your-work-and-life-david-rogers/1119303640?ean=2940149174379

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/waging-business-warfare-lessons-from-the-military-masters-in-achieving-competetive-superiority-revised-edition-david-rogers/1119079991?ean=2940149284030

Mastery models in your life should discuss ways in which their confidence in themselves helped them to achieve their desired goals, and their errors and failures they had before eventually performing at a mastery level, and the work they put in to reach success. Ideally, the mastery model will be a warm, enthusiastic, and encouraging person who is trying to help someone else learn new behaviors after possible years doing things in a different, less productive way.

Mastery models in your life should discuss ways in which their confidence in themselves helped them to achieve their desired goals, and their errors and failures they had before eventually performing at a mastery level, and the work they put in to reach success. Ideally, the mastery model will be a warm, enthusiastic, and encouraging person who is trying to help someone else learn new behaviors after possible years doing things in a different, less productive way.