The mind imitates what it first imagines.

Writers and artists often reflect on their careers and wish they were doing better—were more skilled, had made more progress, and were experiencing important successes more often. All the while they are wishing, they are in possession of a highly refined ability that may hold the answer to their wishes. When we possess the potential to perform something, if we vividly and in detail imagine ourselves performing it successfully, our potential will be released and we will perform nearly the same way during the actual performance as we did in our imagined performance. This insight—this technique—can help a writer or artist achieve greater success.

If there is one unique skill writers and artists possess in abundance, it is making vivid visual images. Images are the basis of the writer’s and artist’s work. They think in images, and the central problem is how to put the image of the thing—the poem, the book, the play, the painting, the sculpture, the building—into a tangible form that satisfies the creator and also appeals to an audience. Can you write a description of a character’s face or of the leaves on a tree or paint them without the ability to visualize images of them in your mind and then to make facsimiles of those images in words and pigments, words and pigments that will recreate for the reader and viewer the very images you had  imagined? Surrealist Salvador Dali liked to use in his work images that came to him when he fell asleep—you can understand why–so he would sit at a table while sleepy, prop his chin with a spoon, and then wait to be awakened when he fell asleep and the spoon fell.

imagined? Surrealist Salvador Dali liked to use in his work images that came to him when he fell asleep—you can understand why–so he would sit at a table while sleepy, prop his chin with a spoon, and then wait to be awakened when he fell asleep and the spoon fell.

Images also affect the writer’s audience because the audience thinks in images too. Even the smallest image is like a photograph the audience mentally sees. In poetry the just right image can make a poem, but just one wrong image can ruin it—that’s how sensitive readers are to images. In her book, The Creative Habit, dancer/choreographer Twyla Tharp tells the story of the difficulty director Mike Nichols was having getting Annie ready for Broadway. A scene that was supposed to get laughs was failing, so Nichols asked famed choreographer Jerome Robbins to fix the scene. Robbins looked at the stage and pointed to a towel hanging at the back of the set. He said, “That towel should be yellow.” The change was made and thereafter the audience laughed at the scene.

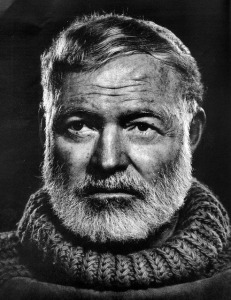

Remembering is at the core of a writer’s repertoire of skills, the writer’s stock in trade. And it is composed of images—remembrance of things past. Artists who paint in studios paint from memory of the landscape, the sunset, the garden. Images, imagination, and intuition go hand in hand. Novelist Thomas Wolfe’s ambition was to turn even the most minor experience he had ever had in life and every image he remembered into words—“those thousands of things which all of us have seen for just a flash…which seem to be of no consequence…which live in our minds and hearts forever.”

So it should not be difficult for you to use your highly-developed image-creating and image-remembering powers to help you achieve your goals—to visualize yourself working diligently to achieve them, and then achieving them with great success. What first occurs in your imagination is a rehearsal for reality. Turn that to your advantage.

So it should not be difficult for you to use your highly-developed image-creating and image-remembering powers to help you achieve your goals—to visualize yourself working diligently to achieve them, and then achieving them with great success. What first occurs in your imagination is a rehearsal for reality. Turn that to your advantage.

The research and practical experience showing that imaginative practice—mentally visualizing performing an action the way you wish to perform it—can actually improve performance—and substantially–is overwhelming. That your mental images can do that is a stunning insight. I can vividly imagine myself running a mile in 3:47, but I will never be able to do it, nor will I ever sing a Puccini aria on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera though I can picture that too. They are beyond my physical capabilities. But when something is within the range of our capabilities–and that range is much broader than we usually believe it to be–the images we hold can have a startling effect on actual performance such as becoming a better and more financially successful writer and artist.

There’s no arena in which the effects of inner images on performance is as widely recognized as athletics. In one landmark study that looked at the effects of imaginative practice on actual performance, basketball free throw shooting was looked at. Participants were divided into three groups. The performance of each participant was measured on the first and last days to see if the experiment led to any improvement. One group practiced shooting for twenty minutes each day for twenty days. A second group didn’t practice at all. The third group spent twenty minutes a day not actually shooting–not touching a basketball at all–but just imagining themselves shooting free throws successfully; standing at the free throw line, looking at the rim, bending their knees, etc. When they “saw” themselves missing, they imaginatively corrected their aim. The group that practiced actually shooting improved their performance by 24% over the twenty days. Not surprisingly, the second group that hadn’t practiced at all didn’t improve at all. But the group that hadn’t actually shot one ball, but practiced in their imagination alone, improved in scoring almost as much as those who actually shot the ball—23%.

Golfers were divided into three groups. Before putting, Group I imagined the ball rolling into the cup. Group II practiced every day, but made no use of imaginative practice. Group III imagined the ball missing the cup. The performance of the group using imaginative practice of the ball rolling into the cup improved 30% between day one and day six. The group that practiced every day, but made no use of imaginative practice also improved, but only 10%. The group that imagined the ball missing the cup showed a decrease of 21% over the six days. These experiments weren’t really “about” free throw shooting or sinking putts at all. They were about the impact of practicing in your mind on your actual performance.

Golfers were divided into three groups. Before putting, Group I imagined the ball rolling into the cup. Group II practiced every day, but made no use of imaginative practice. Group III imagined the ball missing the cup. The performance of the group using imaginative practice of the ball rolling into the cup improved 30% between day one and day six. The group that practiced every day, but made no use of imaginative practice also improved, but only 10%. The group that imagined the ball missing the cup showed a decrease of 21% over the six days. These experiments weren’t really “about” free throw shooting or sinking putts at all. They were about the impact of practicing in your mind on your actual performance.

Mental patients have improved their condition by imagining that they are perfectly normal and then behaving in exactly the way they imagine. Hospitalized patients took a personality test. Then they took the same test a second time. The second time they were instructed to answer the questions not as they normally would, but as they would were they a typical, well-adjusted person on the outside. To do that they had to form and hold in mind an image of how a well-adjusted person would act. Seventy-five percent showed improved test performance. Some of the improvements were dramatic. Imagining how a normal person would act, many began to act like, and feel like, a well-adjusted person functioning in the outside world. That affected their recovery.

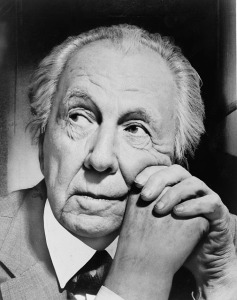

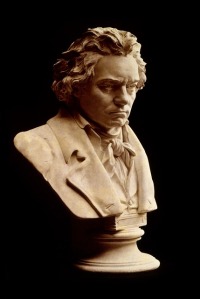

The famous concert pianist Arthur Schnabel took lesson for only seven years compared to the twenty or twenty five years many pianists take. And while even the most successful concert pianists generally spend hours every day  practicing, Schnabel hated practice and spent little time on it. He was asked how he could practice so little and be so great. “I practice in my head,” he said. Mozart made very few corrections on his compositions. Before he began to put notes on paper he already had a complete mental picture of what they would be. He wrote:

practicing, Schnabel hated practice and spent little time on it. He was asked how he could practice so little and be so great. “I practice in my head,” he said. Mozart made very few corrections on his compositions. Before he began to put notes on paper he already had a complete mental picture of what they would be. He wrote:

…provided I am not disturbed, my subject enlarges itself, becomes methodized and defined, and the whole, though it be long, stands almost complete and finished in my mind, so that I can survey it, like a fine picture or a beautiful statue, at a glance.

- Hold clearly and steadily in mind throughout the year, throughout the day, images of what you aspire to—the writer or artist you wish to be; to produce exceptional work, to write beautiful or persuasive or moving text, to draw or paint more skillfully than ever. It is first in your imagination that you launch yourself toward your highest aspirations. Decide what they are, and then vividly imagine what you want to have happen. Then pursue them with determination in the way you have vividly imagined them.

- Regularly, for fifteen minutes every day (weekends included) imagine the actions you want to take:

Vividly

In specific detail

Step by step

Over and over.

Repetition fixes an image of the ideal performance in your mind.

- Imagine that writing or painting come easily to you—the ideas are clear, the words and brushstrokes come out of you without effort, fluently, as if on their own. Now there they are on the page and canvas exactly as you want them.

- Imagine you’ve found the solutions to artistic problems that till now you haven’t been able to solve. Imagine that you have overcome obstacles that have been blocking you.

- Delete from your mind every image of failure such as imagining yourself receiving a rejection from an editor or gallery and add only images of success. Do that continually and relentlessly. Get rid of images of yourself as a failure, not competent, not up to the writer’s or artist’s tasks—discouraged, disappointed, weak.

- When an image of failure enters your mind—as it will (you are human)–replace it with a more optimistic image of success. If you visualize yourself failing, you sabotage yourself and increase your chances of doing that, just as putters who visualize themselves missing the hole are prone to missing the hole. You are actually practicing failure.

- It isn’t necessary to be relaxed when you’re visualizing. In fact, some tension, some excitement, makes you more alert and focused.

- Visualize yourself working as skillfully as you would like in the ideal work setting you would like, during the hours you would like, for the length of time you would like.

- Then, focus your mind on the task ahead of you often. Think of it again and again. Then, immediately before you perform it, clearly visualize yourself performing the action perfectly—the right words, the right imagery, the right form and technique, right style, the meanings you intend.

- Do it–whatever it is—precisely the way you have imagined doing it. Images, no matter how vivid, will come to nothing unless you translate them into actions that conform to the images, so let the images guide you.

- Be enthusiastic and confident. Enthusiasm and confidence add zest to your images.

- Combine your images with thinking aloud. For example saying aloud as you are visualizing, “I will work smoothly and efficiently. Everything will go well. I don’t anticipate problems, but if there are any, I’ll be able to solve them.”

Add Feelings

The technique of adding feelings is adding emotions of successful achievement to what you have visualized as though you’ve already succeeded. This is a very effective motivational technique. You’re not interested now in the mental images of the way you will achieve the goal. Rather you’re letting yourself feel what you will feel when you have reached the goal—or solved writing or artistic problems or made progress. Having done those things you’ll feel satisfaction, pleasure, pride, a sense of accomplishment and self-confidence; you’ll feel relieved, and possibly excited, overjoyed, elated, and thrilled. Whatever you imagine you will feel then, feel it now in anticipation. Don’t wish and hope you’ll succeed, but treat success as an accomplished fact. It’s done, and you have already succeeded and are glowing with positive emotions. Feel the physical sensations of that glow, that sense of warmth, the excitement, the energy, the heightened perception, the sharpness. Imagining what you will feel when you succeed fuels your motivation to succeed because that is how you want to feel. Congratulate yourself: YOU DID IT and now you are enjoying the feelings.

The technique of adding feelings is adding emotions of successful achievement to what you have visualized as though you’ve already succeeded. This is a very effective motivational technique. You’re not interested now in the mental images of the way you will achieve the goal. Rather you’re letting yourself feel what you will feel when you have reached the goal—or solved writing or artistic problems or made progress. Having done those things you’ll feel satisfaction, pleasure, pride, a sense of accomplishment and self-confidence; you’ll feel relieved, and possibly excited, overjoyed, elated, and thrilled. Whatever you imagine you will feel then, feel it now in anticipation. Don’t wish and hope you’ll succeed, but treat success as an accomplished fact. It’s done, and you have already succeeded and are glowing with positive emotions. Feel the physical sensations of that glow, that sense of warmth, the excitement, the energy, the heightened perception, the sharpness. Imagining what you will feel when you succeed fuels your motivation to succeed because that is how you want to feel. Congratulate yourself: YOU DID IT and now you are enjoying the feelings.

Every day—once, twice, three times, four times — let yourself feel the strong emotions you’ll feel when you’ve succeeded.

© 2015 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

or

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

or