Part I

I’m writing a book that says high achievement for artists and writers is within reach. It describes eight qualities creators need if they are to excel. If even one quality is missing, they will not excel. Day after day for a week I made no progress on one section. I would sit down to work at the computer and find myself fiddling around mindlessly for a few hours, then going down to the kitchen for a snack or looking around for someone to talk to, or I’d do laundry or something and after a while would go back upstairs to the computer with every intention of working on that section only to find myself  checking the sports scores. Then I’d quit for the day and feel that nagging dissatisfaction with myself that writers and artists so often feel. Finally I sat down on my recliner to try to get to the bottom of this and asked myself, “What’s the problem?” and I immediately answered, “That section is too easy for me.”

checking the sports scores. Then I’d quit for the day and feel that nagging dissatisfaction with myself that writers and artists so often feel. Finally I sat down on my recliner to try to get to the bottom of this and asked myself, “What’s the problem?” and I immediately answered, “That section is too easy for me.”

Most people in the world can be divided psychologically into two broad groups. Probably you are in one group, just as I am. There is the minority who set and pursue challenges for themselves and are willing to work hard to achieve something, and then the majority who don’t care about challenges all that much and don’t work hard. Those two groups are to be found among artists and writers everywhere in the world, just as they can be found among students, accountants, businessmen and women, athletes, and people in any other field. Mozart was a tremendous worker who practiced, performed, and gripped a quill pen to compose so many hours that by the age of 26 his hands were deformed.

The first group that sets out in pursuit of challenges possesses a distinct kind of motivation, a specific kind of measurable psychological need that the group that is indifferent to challenges lacks. That need is called Achievement Motivation, Success Motivation, or The Need to Achieve, and the people who have it are those who reach higher achievements than most other people, certainly higher than those who don’t care. (Much of the initial work on  Achievement Motivation was done by psychologist David C. McClelland). The achievers are more successful artists and writers, just they are more successful students, physicians, athletes, salespeople and business executives. It is naïve of a creator to think talent alone will take a person to great heights. Most teachers of writers and artists will tell you that it is rarely the most talented pupil who dazzled the class that they hear and read about later. They hear about the one who was the most determined to succeed and the most dogged—a member of the first group.

Achievement Motivation was done by psychologist David C. McClelland). The achievers are more successful artists and writers, just they are more successful students, physicians, athletes, salespeople and business executives. It is naïve of a creator to think talent alone will take a person to great heights. Most teachers of writers and artists will tell you that it is rarely the most talented pupil who dazzled the class that they hear and read about later. They hear about the one who was the most determined to succeed and the most dogged—a member of the first group.

So it seems to me extremely important if you want to enjoy more success, however you define success, to understand what high success people are like, so if you wish, you can become more like them and achieve more creatively and find more fulfillment. If they are in the business world, achievement motivated men and women have high career aspirations just as achievement motivated writers and artists are ambitious and have high career aspirations. Author Ernest Hemingway was as ambitious as anyone. An unbelievably hard worker, he wanted nothing less than to be the world’s greatest writer. And in 1954 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize, he was. Vincent van Gogh said that while he wasn’t successful during his life—he sold only one painting in his lifetime and traded another for brushes–one day he would take his place among the immortals. In the work world achievement motivated people get more raises and are promoted rapidly. If they are unemployed they get new jobs more quickly than less motivated people. Companies that employ a lot of them prosper.

If you are in the first group—achievers—I know you very well. I know how you think. I know how you act. I know your values. I know something about how your parents reared you. I know what color clothes you prefer to wear.

First of all, you are definitely goal-directed, and it’s no secret to you that achieving goals will require that you follow a linked series of steps over an often long period of months or years as you progress from beginner to expert, and sometimes amateur to professional. P.G. Wodehouse said, “Success comes to a writer, as a rule, so gradually that it is always something of a shock to him to look back and realize the heights to which he has climbed.”

First of all, you are definitely goal-directed, and it’s no secret to you that achieving goals will require that you follow a linked series of steps over an often long period of months or years as you progress from beginner to expert, and sometimes amateur to professional. P.G. Wodehouse said, “Success comes to a writer, as a rule, so gradually that it is always something of a shock to him to look back and realize the heights to which he has climbed.”

From the start you exert yourself and mobilize more energy to reach your goals than other people. And you are able to persist steadily without interruption whereas poorly motivated writers and artists have low energy and will interrupt their work more often and not engage in it for long periods, even years. That can have a detrimental effect: if you neglect an activity for just 48 hours you function much less effectively when you resume the activity. While achievement people are hard persistent workers, they need not fill their entire day with work and are able to cut out and enjoy leisure time. At least in America most people work at least 7 hour days and must travel to and from work, but professional writers usually work at home about four hours, 16.7 % of the day, leaving 20 hours for other things (though some, like prolific novelist Philip Roth, work all the time).

A long gestation period is required before artists and writers are fully developed and performing at their peak, and during that period you spend your time actively thinking about how to do things better. You constantly talk about doing things better. You’re concerned with getting better all the time. You take classes, you study, you read, you learn. In other words, you are dominated by what is called An Urge to Improve. It’s not difficult to understand why people who constantly think about doing better:

A long gestation period is required before artists and writers are fully developed and performing at their peak, and during that period you spend your time actively thinking about how to do things better. You constantly talk about doing things better. You’re concerned with getting better all the time. You take classes, you study, you read, you learn. In other words, you are dominated by what is called An Urge to Improve. It’s not difficult to understand why people who constantly think about doing better:

- Are apt to do better at what they’re interesting in doing better

- Prefer working in situations where they can tell easily if they are improving or aren’t

- Keep track of their performance so they can tell if they’re in fact doing better

If you are an achiever, the goals you set are one or more of four types:

One, you compete with yourself, trying to achieve more in the future than you’ve achieved in the past. Is this true of you? If it is, you stay interested by aiming higher and higher. Once you’ve achieved a goal, the goal loses its luster and you now want something more. You had an essay published. That’s over and done; now you’ll write a book.

Two, you compete with others. You may not like it, but unless you do your creative work solely for the joy of it, you have to compete. Hundreds of writers, possibly thousands, are trying to get their stories in the same magazines as you and as many artists are trying to get their work shown in the same galleries. As novelist Doris Lessing said: “You have to remember that nobody ever wants a new writer. You have to create your own demand.” No one wants a new painter either. And so to draw attention to yourself in a cluttered field of one talented person among many talented people, you must develop the competitive survival skills of the showman and self-promoter.

The necessity of competing needn’t cause anxiety if you learn to be dispassionate and non-attach. Then you see competing as just another challenge and role, the role of the marketer of your work, a set of skills that can be learned, the logical conclusion of all your development and all your work.

Three, you engage in a long-term involvement over the long haul, and four, you pursue unique accomplishments–definitions of the work of writers and artists.

You have sub-goals which will lead in an orderly way to the achievement of your major goals. For example, you know that to do as well as you hope, you’ll need to acquire more and more knowledge of your craft throughout your career. Knowledge is not quite everything, but almost. Writers and artists of all kinds draw from all the cumulative knowledge they’ve acquired. They do that sometimes consciously, sometimes spontaneously. What they know is reflected in their every word, every turn of phrase, every image, every idea, and every choice of color and perspective and every brush stroke. So it is incumbent on them if they are to excel to learn more and more about their craft, including how it’s done and how others have done it.

You have sub-goals which will lead in an orderly way to the achievement of your major goals. For example, you know that to do as well as you hope, you’ll need to acquire more and more knowledge of your craft throughout your career. Knowledge is not quite everything, but almost. Writers and artists of all kinds draw from all the cumulative knowledge they’ve acquired. They do that sometimes consciously, sometimes spontaneously. What they know is reflected in their every word, every turn of phrase, every image, every idea, and every choice of color and perspective and every brush stroke. So it is incumbent on them if they are to excel to learn more and more about their craft, including how it’s done and how others have done it.

You take a futuristic view and are a long-range planner who keeps his/her goals in mind continually. They are never out of your mind very long. (In itself, this makes you exceptional because most people have very little idea of what their goals are and don’t think of them often.) The more important the goal is to a low-motivated person, the less interested in it he becomes. He loses focus on what’s important. But the more important it is to you, the achiever, the more challenging and therefore the more interesting to you it is. As it becomes ever more important it becomes ever more challenging and ever more interesting.

It’s worth remembering that to an achievement motivated person like yourself failure to achieve a goal makes the goal more attractive, not less. Failure doesn’t devastate you, but pushes you to greater effort because now it is even more of a challenge, and you thrive on challenges. You try again. And then again and again tenaciously until you succeed, whereas a less strongly motivated writer or artist may not try a second time and never reach success.

You are aware that reaching your goals depends on how difficult they are in relation to your capabilities. The ideal you’re trying for is to match your abilities perfectly with your goals, your abilities equipping you to achieve them all. If you lack the ability, you cannot reach the goal. Simple tasks and very difficult tasks are interesting to people with low motivation, but not to those with achievement motivation like yourself. You’re drawn to goals that are moderately difficult—not too easy; not too hard, but a little out of reach. Goals like that motivate you the most.

It’s been said that if writers were good businessmen, they’d have too much sense to be writers, and John Steinbeck said the profession of book writing makes horse racing seem like a solid, stable business, and the same is true of painting, dancing, and acting. If you’re an achievement motivated writer or artist you won’t even try to reach goals that in your judgment of your own capabilities you don’t have at least a 30% chance of reaching. I submitted a manuscript to a publisher with the odds of publication statistically about 3,000 to 1 against. But I was confident and thought I had a 30% chance. I was right and the book was published.

You will not pursue goals that aren’t challenging enough. Sure things hold no excitement for you. They’re not interesting, just as the section of the book I’m writing is too easy for me. So you spice things up to make the goals more challenging, sometimes making the sculpture or the novel you’re working on more complicated, more ambitious, something, you’ve never tried before, for example. If something is important to the achiever, she will sometimes work days or weeks non-stop. But if it isn’t, she’ll avoid work. She’ll go fishing.

You will not pursue goals that aren’t challenging enough. Sure things hold no excitement for you. They’re not interesting, just as the section of the book I’m writing is too easy for me. So you spice things up to make the goals more challenging, sometimes making the sculpture or the novel you’re working on more complicated, more ambitious, something, you’ve never tried before, for example. If something is important to the achiever, she will sometimes work days or weeks non-stop. But if it isn’t, she’ll avoid work. She’ll go fishing.

Think about your three main writing/art goals at this time. Your crucial goals should always be held clearly in mind so that if I asked you could quickly say…

“No doubt about it, my major overriding goal now is…

“My second most important goal is…

“Also very important is…

Do you feel all in all you have a 30%-65% chance of reaching them? (I’m asking you if they are moderately difficult goals, the achiever’s aim.)

Part II

You work in intense, concentrated spurts (which studies find now is the most effective way to work). Other people often marvel at your capacity for sustained effort. They ask, “What do you have going for you that you can stick to it and never seem to tire?” It’s because you are achievement motivated. But when the work is done, you put it completely out of mind and want nothing more to do with it. You want to go on right away to the next moderately difficult project, or you want to go to the beach and forget all about your work. The change from hard work to a total disinterest in work is so extreme at times that your significant other will say to you, “One minute you’re a ball of fire, the next I can’t get you to do a thing.” A research study found that professional writers couldn’t remember what they had just written, but amateurs could remember very clearly what they had written.

You consider your goals very carefully if you are achievement motivated. You “research the environment,” gathering information wherever you can and consider the probability of success of a variety of alternatives and try to find goals and tasks that will excite you. Should you continue working on the project you’ve started or stop and begin something else? One thing experienced creative people are good at is knowing when something is not going to work out, and if it isn’t, they don’t hesitate to junk it. Writers have been known to write an entire book, then decide they don’t like it and put it in a drawer and forget about it. Should you get help? Getting help is a sign in itself that you’re trying to reach the goal. Should you try something completely different such as a new style, a new technique, a new market for your work? You take time to reflect on your career, your strengths, your weaknesses, your ambitions, and your possible future continually.

When you set goals you spend more time thinking about what it would be like to succeed than what it would be like to fail. You don’t dwell on failure, only on success. And what is success to you? It is reaching excellence. Producing excellent work is far more important to you than prestige. But prestige is more important than excellence to those whose motivation is low, and they dwell on the possibility of failure.

When working in a group setting and asked to pick someone to help them solve a problem, low motivated people will tend to choose friends, but the most highly motivated will choose for a partner someone who’s more able than they are, friend or no friend.

You are task-oriented, a hard-worker no matter what the situation is—writing, painting, doing chores, planning a novel, assembling a dresser. The low-motivated writer or artist avoids working hard whenever he can. Also, highly motivated people, surprisingly, are better able to recall tasks they didn’t finish. And if they’re given a chance, they will return and compete those tasks. Even tasks that were interrupted many years before—the so-called Zeigarnik Effect. Achievers are not comfortable with unfinished business.

You prefer to take personal responsibility for outcomes rather than to leave the outcome to chance. You want outcomes to be the result of your own efforts and your own skills. You are not a gambler if no personal skills are involved and if winning and losing is a matter of luck and not of skill. Lotteries and slot-machines aren’t appealing because no skill is involved. If you were able to throw dice with a 1 in 3 chance of success or work on a problem with the same odds, you will choose to work on the problem because the result would be dependent on your abilities rather than chance.

Since achievement motivated people are always interested in improving their performance, they crave feedback on how well they are doing. The feedback must be (1) rapid and (2) specific. They want to know now and they want to know why. They are writers and artists who want constructive criticism.

So if you wish to be more of an achieving writer and artist:

- Pursue moderately difficult goals that require: a) doing better, b) competing for success, and c) engaging in projects that need long-term involvement and unique accomplishments.

- Get in the habit of researching your environment, looking for many sources of useful information you’ll need to set reasonable and attractive goals.

- Don’t dwell on failure; dwell on success. Think of what it will be like when you’ve succeeded.

- Be always expanding your knowledge. Set knowledge development learning goals.

- Take a long-term view of your writing, your painting, your sculpting.

- Be interested in excellence for its own sake.

- Work intensely in spurts and persist in the face of failure.

- Carefully consider the probability of success achieving each of your goals.

- Take personal responsibility for your work and your career.

- Get rapid and specific feedback on your efforts continually.

- Get help

- Be thinking all the time of how to do things better.

- Place your confidence in your own abilities and your own hard work.

I’ll have to find a way to make writing that section of the artist’s and writer’s book more interesting—more moderately difficult–so I can work harder and finish it. We’ll see what happens.

© 2015 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

www.mentorcoach.com/rogershttp://www.mentorcoach.com/positive-psychology-coaching/interviews/interview-david-j-rogers/

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fighting-to-win-samurai-techniques-for-your-work-and-life-david-rogers/1119303640?ean=2940149174379

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/waging-business-warfare-lessons-from-the-military-masters-in-achieving-competetive-superiority-revised-edition-david-rogers/1119079991?ean=2940149284030

Bellow, an anthropology major, or innovative French novelist/ screenwriter/essayist Alain Robbe-Grillet, an agronomist, or may not have attended college at all. Many great writers, like Nobel winner Ernest Hemingway, had no interest in attending college, and many others, like Nobel winners William Faulkner and playwright Eugene O’Neill didn’t take college seriously (well that’s probably true of 30 or 40% of all college students), and quit it because they thought it was not only not helping them, but holding them back. And I’m guessing that not more than, let’s see, two of you painters attended the Sorbonne, and some possibly never attended any art school. Yet you’re capable and have had writing and painting success. Your work has been published and art works have been shown. Some of you are professionals earning a substantial living.

Bellow, an anthropology major, or innovative French novelist/ screenwriter/essayist Alain Robbe-Grillet, an agronomist, or may not have attended college at all. Many great writers, like Nobel winner Ernest Hemingway, had no interest in attending college, and many others, like Nobel winners William Faulkner and playwright Eugene O’Neill didn’t take college seriously (well that’s probably true of 30 or 40% of all college students), and quit it because they thought it was not only not helping them, but holding them back. And I’m guessing that not more than, let’s see, two of you painters attended the Sorbonne, and some possibly never attended any art school. Yet you’re capable and have had writing and painting success. Your work has been published and art works have been shown. Some of you are professionals earning a substantial living. his first picture at the age of 36 and exhibited in his first show at 40. His earliest paintings were technically incorrect and unsophisticated as the work of a beginner usually is. The forms were stiff and simple; the proportions were inaccurate, and the perspectives were wrong. But in his work there was “something” that drew the attention of critics and the public—the honesty in the works, a directness that came right out of his obvious joy in the act of creation. He was an advanced autodidact and did things that other unschooled artists did not usually do, and conventionally trained painters did not do. Paint which in a run-of-the-mill painting of a beginner would be thin and dry is applied with rich body. Colors that would be anemic or muddy in the ordinary newcomer’s work were clear in Rousseau. His work continued to grow in popularity. His paintings created a world of enchantment.

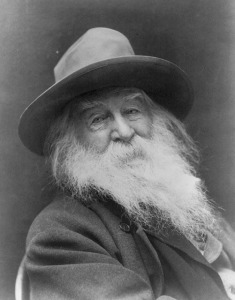

his first picture at the age of 36 and exhibited in his first show at 40. His earliest paintings were technically incorrect and unsophisticated as the work of a beginner usually is. The forms were stiff and simple; the proportions were inaccurate, and the perspectives were wrong. But in his work there was “something” that drew the attention of critics and the public—the honesty in the works, a directness that came right out of his obvious joy in the act of creation. He was an advanced autodidact and did things that other unschooled artists did not usually do, and conventionally trained painters did not do. Paint which in a run-of-the-mill painting of a beginner would be thin and dry is applied with rich body. Colors that would be anemic or muddy in the ordinary newcomer’s work were clear in Rousseau. His work continued to grow in popularity. His paintings created a world of enchantment. writer who couldn’t hold a job into–through a “liberation of language” never seen before on earth—one of the greatest poets the world has ever known. Prior to his first book– Leaves of Grass–he seemed to be a very untalented man. Before becoming the” father of American poetry,” he worked as a carpenter (building his own home) and as an elementary school teacher, printer, editor, shopkeeper, and in the world of newspapers, paled around with artists and sculptors, attended operas (said he learned more about writing from operas than from anything else), studied history and astronomy on his own, read voraciously, and believed in self-help and self-education. He said that during those years before Leaves of Grass when he was writing “conventional verse” he was “simmering, simmering, simmering.” This man who wrote, “I have not once had the least idea who or what I am” developed in those mystical six years a vision and style that no one since has been able to duplicate. His poetry startled the literary world and started a new direction in poetry. Readers were astonished.

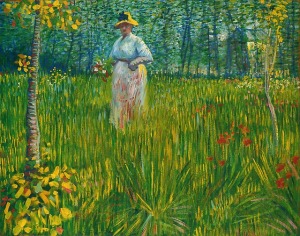

writer who couldn’t hold a job into–through a “liberation of language” never seen before on earth—one of the greatest poets the world has ever known. Prior to his first book– Leaves of Grass–he seemed to be a very untalented man. Before becoming the” father of American poetry,” he worked as a carpenter (building his own home) and as an elementary school teacher, printer, editor, shopkeeper, and in the world of newspapers, paled around with artists and sculptors, attended operas (said he learned more about writing from operas than from anything else), studied history and astronomy on his own, read voraciously, and believed in self-help and self-education. He said that during those years before Leaves of Grass when he was writing “conventional verse” he was “simmering, simmering, simmering.” This man who wrote, “I have not once had the least idea who or what I am” developed in those mystical six years a vision and style that no one since has been able to duplicate. His poetry startled the literary world and started a new direction in poetry. Readers were astonished. van Gogh was self-made. He had only one year’s total training from instructors, but studied ceaselessly on his own, the autodidact of autodidacts. He had tremendous faith in the future of his work, and felt it was worth sacrificing everything for it. He was a harsh self-critic, considering many of his paintings now accepted as masterpieces mere studies. At the time of his death he had sold one painting and traded another for brushes, had been represented by just a few dealers, had participated in a half-dozen shows, and had dissuaded critics from writing about his work. Few artists of any kind have made themselves as knowledgeable or clear-sighted about their art, or have a more developed understanding of painting. He rarely signed his works, believing that to do so was arrogant, and that an artist should work humbly. He had a short but prodigious career, leaving behind a legacy of more than 2,000 paintings and drawings at his death at thirty-seven.

van Gogh was self-made. He had only one year’s total training from instructors, but studied ceaselessly on his own, the autodidact of autodidacts. He had tremendous faith in the future of his work, and felt it was worth sacrificing everything for it. He was a harsh self-critic, considering many of his paintings now accepted as masterpieces mere studies. At the time of his death he had sold one painting and traded another for brushes, had been represented by just a few dealers, had participated in a half-dozen shows, and had dissuaded critics from writing about his work. Few artists of any kind have made themselves as knowledgeable or clear-sighted about their art, or have a more developed understanding of painting. He rarely signed his works, believing that to do so was arrogant, and that an artist should work humbly. He had a short but prodigious career, leaving behind a legacy of more than 2,000 paintings and drawings at his death at thirty-seven.