Artists Starting The Day

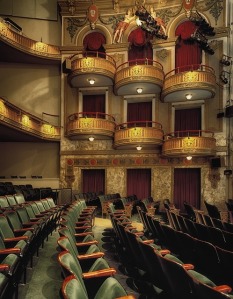

A novelist sits down at the computer to begin the day with an idea in mind, and a painter organizes her brushes before she begins. An actor is in a theater lobby trying to understand how she will play a complicated new role, and a ballet dancer is on a bus on his way to ten o’clock practice. He has worked so hard so long—since childhood—that his feet throb day and night.

A novelist sits down at the computer to begin the day with an idea in mind, and a painter organizes her brushes before she begins. An actor is in a theater lobby trying to understand how she will play a complicated new role, and a ballet dancer is on a bus on his way to ten o’clock practice. He has worked so hard so long—since childhood—that his feet throb day and night.

They might be anyone, but they’re not. They are artists and they are different and they know they are, and have always known. They have different points of view, habits, values, routines, and preoccupations than even the people closest to them, and as they perform their art today, carrying out their chosen roles, they will exercise talents that not everyone possesses. All the skills they’ve struggled to develop, and all the hopes and ambitions guiding them, and their entire being, will be brought to bear today.

To Be an Artist

Artists possess traits and qualities that equip them for the artist’s creative life. Whether you find them in big cities or remote jungles or on farms or in desert tents, in any of the four hemispheres, you will also find them generally to be quite similar: to have varied interests and to be persistent in the face of obstacles and disappointments. They are dogged, determined, resourceful, open-minded, undeviating, tolerant of ambiguity and novelty, tenacious, and tremendously independent and self-reliant. And they are also self-confident, resilient risk-takers with good memories, and the hardest workers on this globe and almost as self-sacrificing and self-demanding as Saint Francis of Assisi. They are complex thinking and feeling people who seek out complexity and who:

Possess extraordinary energy and an addiction to work (A characteristic of artists that distinguish them from others is their capacity for hard sustained effort. No outstanding creative achievement has ever been produced without a great deal of conscious work on the part of the creator. When artists are fully functioning they work at white heat for an hour, a day, a week, or months or years.)

Possess extraordinary energy and an addiction to work (A characteristic of artists that distinguish them from others is their capacity for hard sustained effort. No outstanding creative achievement has ever been produced without a great deal of conscious work on the part of the creator. When artists are fully functioning they work at white heat for an hour, a day, a week, or months or years.)

Can produce tremendous volumes of work (Balzac wrote 95 novels before his death at 51. Picasso produced a quarter million works of art. Novelist Thomas Wolfe sometimes wrote 5,000 words in a night. Not always, but usually, the greatest artists are also the most prolific.)

Are willing to sacrifice for the sake of their art without hesitation (American Impressionist Mary Cassatt, possibly the greatest woman painter of the nineteenth century, kept royalty waiting until she had finished her day’s work. Hemingway said he had to ease off making love when he was writing hard because the two things were “run by the same motor.” Nobel Prize novelist Toni Morrison said, “The important thing is that I don’t do anything else.” Another Nobel novelist, Saul Bellow, said writing was more important to him than anything, including his family.)

Value authenticity, integrity, and sincerity (How many other occupations involve a quest for truth?)

Are oriented to the fullest development of their skills (You must never lose the belief that you have the ability to carry out skills needed to produce quality art successfully. Developing skills leads to competency, then to expertise, then excellence, then greatness. If you feel you have the skills you are less likely to be haunted by self-doubt, and your art flows more freely. If you ask yourself “Do I have the skill?” and you answer “No I don’t,” you’ll have to learn the skill. There are any number of ways to accomplish that.)

Are oriented to the fullest development of their skills (You must never lose the belief that you have the ability to carry out skills needed to produce quality art successfully. Developing skills leads to competency, then to expertise, then excellence, then greatness. If you feel you have the skills you are less likely to be haunted by self-doubt, and your art flows more freely. If you ask yourself “Do I have the skill?” and you answer “No I don’t,” you’ll have to learn the skill. There are any number of ways to accomplish that.)

Are preoccupied with technique and style (The public isn’t meant to notice an artist’s technique, but other artists are aware of it immediately. The first thing you notice about a great artist is a distinctive style.)

Are ambitious and competitive (Art is as competitive as a Yankees-Red Sox game.)

Are resilient and able to overcome obstacles and persevere (Artists persist doggedly, however difficult or frustrating the physical and mental effort of pursuing their goal might be. After a success, your expectations of future success rise. When you see you are overcoming obstacles and making steady progress and reaching your goals, your confidence increases, sometimes phenomenally.)

Value originality (A work must be original if it’s to be considered artistic.)

Must have the ability to establish rapport with and hold an audience (To succeed, all works of art need a theatrical element.)

Must have a business sense (Artists have a career to manage, and responsibilities and expenses, and intangible rewards are not the only rewards. When you receive rewards your sense of well-being and hopefulness rise. All arts involve salesmanship.)

Have a practical, problem-solving intelligence (Each day every artist on earth solves a hundred complex problems. Artists do not spend their days working on easy problems; they work on problems that are hard for them. That’s how they create work that has never been seen before and continue to expand their abilities at the same time.)

Have a practical, problem-solving intelligence (Each day every artist on earth solves a hundred complex problems. Artists do not spend their days working on easy problems; they work on problems that are hard for them. That’s how they create work that has never been seen before and continue to expand their abilities at the same time.)

Have an artistic vision and heightened perception (To the artist the world is inexhaustibly rich with aesthetic potential. To painters and photographers a leaf is much more than a leaf; an actor’s frown signifies more than a frown; a single word, a single syllable, holds untold riches for a poet.)

Have a capacity for self-criticism and objectivity about their work and their abilities (Artists learn to lay their egos aside as they would any other impediment.)

Are sensitive to life and open to experience (Curious, they plumb what is outside them in the world and their own thoughts, feelings, and emotions. Whatever happens to them, they never forget it.)

Strive for competence and constant improvement (An artist is never content very long.)

Value independence (All artists must be allowed to move in their own direction under their own power.)

Are more self-confident, rebellious, bold, and daring than the vast majority of people (If you lose those things, you lose your talent as well.)

Have the ability to focus (Artists are capable of ferocious concentration, losing all sense of time and place, conscious only of the work before them.)

Are playful and value the simple and the unaffected (Artists are in love with simplicity.)

Have an abundance of physical strength and stamina (Architect Buckminster Fuller was often unable to stop working until he dropped from exhaustion. Work poured out of Da Vinci in a torrent. Often it is the end of the artist’s endurance that stops his working day.)

Are far more self-disciplined in matters concerning work than most people in other fields

Are able to adapt and make adjustments (An experienced artist has learned when to stop and begin again when something isn’t working.)

Are able to adapt and make adjustments (An experienced artist has learned when to stop and begin again when something isn’t working.)

Are studious in the sense of studying to develop their craft (All artists study and all are self-taught to a greater or lesser degree.)

Take luck, the breaks, and good or bad fortune into account (Good luck often follows persistence. A failure or wrong direction or bad luck may lead to something fruitful later on. A “wrong” word in a sentence may prove to be the perfect word.)

Must be patient, because all artists who reach high excellence will have done so via a long period of learning and application while pushing themselves upward to it.

Have a strong belief in, and respect and enthusiasm for their art

Are deep-feeling, emotionally rich

The writer at the computer, the painter sorting brushes, the actor in the lobby, and the dancer with sore feet needn’t feel lonely as they start the day because possibly very near are others who lead similar lives and are very much like them.

© 2014 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

or

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

or