You Don’t Have to Feel Good to Have a Delightfully Productive Day

I follow sports closely, and it surprises me how often swimmers, tennis players, track stars, basketball players, and other athletes perform their record best on the very days they are not feeling fit physically or emotionally. They feel “off” but nevertheless they compete and often they excel.  I think of the famous Michael Jordan “flu game” when he had to be carried off the floor after the game with the flu by a teammate, yet scored 38 points and led the Bulls to victory. “Probably the most difficult thing I have ever done,” said Jordan.

I think of the famous Michael Jordan “flu game” when he had to be carried off the floor after the game with the flu by a teammate, yet scored 38 points and led the Bulls to victory. “Probably the most difficult thing I have ever done,” said Jordan.

That illogical phenomenon of feeling unprepared and yet excelling also applies to people in the arts. Robert Boice said, “Beyond doubt, creative writers who begin a project before feeling prepared or motivated achieve more quantity and quality.” Feeling out of sorts used to stop me. When I wasn’t feeling right, I’d think, “Why even try?” But now, because I am familiar with athletes not feeling good but performing so well, when I feel not ready at all to write, I become optimistic and confidently sit down at the computer and expect a productive day, and usually have one.

You will be more productive if like those athletes you don’t make your mood the dictator of your performance, but simply however you feel you do your work. Don’t live by how you feel. Everyone  would prefer to be cheerful and happy, but as far as creative work is concerned, how you feel is secondary. What matters most are the requirements of the craft you have committed yourself to, and one requirement is day after day to put out effort to achieve your creative goals. It seems to me that one constant goal that is shared by most people in the arts is to develop your in-born talents to the fullest and that another requirement is to produce finished works. When you see your talents growing and you are producing original works regularly and everything is meshing, you are at your best, and you know it.

would prefer to be cheerful and happy, but as far as creative work is concerned, how you feel is secondary. What matters most are the requirements of the craft you have committed yourself to, and one requirement is day after day to put out effort to achieve your creative goals. It seems to me that one constant goal that is shared by most people in the arts is to develop your in-born talents to the fullest and that another requirement is to produce finished works. When you see your talents growing and you are producing original works regularly and everything is meshing, you are at your best, and you know it.

In the nineteen-sixties a number of America’s excellent poets who knew each other well felt that to write their best poetry–to be in what they thought was the ideal mood for writing verse– they had to feel deeply depressed. That was their philosophy and what they talked and  corresponded about. Nurturing depression in and out of psychiatric hospitals, some of them committed suicide including John Berryman and Randall Jarrell. Poets Sylvia Plath and Ann Sexton were friends and felt the same. They talked to each other often, and also committed suicide.

corresponded about. Nurturing depression in and out of psychiatric hospitals, some of them committed suicide including John Berryman and Randall Jarrell. Poets Sylvia Plath and Ann Sexton were friends and felt the same. They talked to each other often, and also committed suicide.

But you don’t have to feel miserable to write a poem or a tragedy or be in love to write a romance. Anton Chekhov said that ironically happy writers write sad things and sad writers write happy things. Gustav Flaubert said that the less writers feel a thing, the more likely they are to express it as it really is. J.D Salinger wrote that ecstatically happy prose writers have disadvantages. They can’t be moderate, temperate, detached, or brief.

Some writers seem so grim and bitter about their need to write. George Orwell said that “Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon one can never resist or understand.” Opera composer Giacomo Puccini said “Art is a kind of illness.” Nobel laureate Ernest Hemingway felt differently. He felt awful when he wasn’t writing, the opposite when he was: “Suffer like a bastard when don’t write, or just before, and feel empty…Never feel as good as while writing.”

Whatever has been said about the relationship between creatives’ state of mind and their performance, writers and painters I know or have read or heard about have found writing or painting the most fulfilling and blissful thing they do.

Whatever has been said about the relationship between creatives’ state of mind and their performance, writers and painters I know or have read or heard about have found writing or painting the most fulfilling and blissful thing they do.

Overview

I have assembled a number of quotations that pertain to many aspects of the lives of people in the arts– their function, their preference for simplicity, their complex nature, and the construction of their work.

The Creative’s Function

It is not coincidental that the remarkable art and architectural critic John Ruskin and novelist Joseph Conrad with his dazzling visual imagery  had the same view of the function of writers and artists. Ruskin: “The whole function of the artist in the world is to be a seeing and feeling creature.”

had the same view of the function of writers and artists. Ruskin: “The whole function of the artist in the world is to be a seeing and feeling creature.”

Conrad: “My task, which I am trying to achieve is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel–it is, before all, to make you see.”

Don’t Complicate Arts That Are So Simple

Usually, over the course of a career, noted practitioners of an art simplify their views of their role.

“What shall I say about poetry? What shall I say about those clouds, or about the sky? Look; look at them; look at it! And nothing more. Don’t you understand that a poet can’t say anything about poetry? Leave that to the critics and the professors. For neither you, nor I, nor any poet knows what poetry is” (Frederico Lorca).

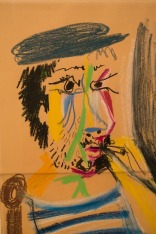

Painter Edouard Manet thought the urge to create is a simple reflex that doesn’t require thought: “There is only one true thing: instantly paint what you see. When you’ve got it, you’ve got it. When you haven’t, you begin again.”

Painter Edouard Manet thought the urge to create is a simple reflex that doesn’t require thought: “There is only one true thing: instantly paint what you see. When you’ve got it, you’ve got it. When you haven’t, you begin again.”

William Faulkner wrote in a highly complicated rhetorical style that is difficult to understand unless you read the sentences over and over. Yet he was the most direct person when he spoke. When asked what he thought made a good writer he said, “I think if you’re going to write, you’re going to write and nothing will stop you.” Saul Below, like Faulkner a Nobel Prize winner, was as direct when he said, “I am just a man in the position of waiting to see what the imagination is going to do next.”

Henry Moore felt that his art had a spontaneity of its own. He believed that if he set out to sculpt a standing man and it became a lying woman, he knew he was making art.

Henri Matisse is reported to have said, “When a painting is finished, it is like a newborn child. The artist himself must have time for understanding it. It must be lived with as a child is lived with, if we are to grasp the meaning of its being” (John Dewy).

The Makeup of Creatives

People generally are fascinated by creatives and want to know what makes them able to produce memorable works. A survey was done dealing with women’s preferences for a husband. The most attractive partner was thought to be a writer. And creatives are self-absorbed and fascinated by themselves.

Creatives express love: Alfred Werner of Marc Chagall: He is a painter of love. He loved flowers and animals, he loved people, he loved love. There is sadness in his paintings, but there is no despair and always a metaphysical hope. “When he paints a beggar in snow, he puts a fiddle in his hands.”

Creatives have complex memories from which their art derives: “The essential factor of development of expertise is the accumulation of increasingly complex patterns in memory” (Andreas Lehmann).

Creatives have complex memories from which their art derives: “The essential factor of development of expertise is the accumulation of increasingly complex patterns in memory” (Andreas Lehmann).

Creatives convey great ideas: “He is the greatest artist who has embodied, in the sum of his work, the greatest number of the greatest ideas” (John Ruskin).

Creatives involve their whole selves in their art: “It is art that makes life, makes intensity, makes importance…and I know of no substitute whatever for the force and beauty of its process “(Henry James).

Creatives are especially perceptive: “It seems to me that the writers who have the power of revelation are just those who, in some particular part of life, have seen or felt considerably more than the average run of intelligent beings…The great difference, intellectually speaking, between one man and another is simply the number of things they can see in a given cubic yard of the world.” (Gilbert Murray.)

How is a Work Made?

Since the earliest civilizations people have been theorizing about creatives among them and the creative process. The first question was: is creative ability a gift from the gods?

Since the earliest civilizations people have been theorizing about creatives among them and the creative process. The first question was: is creative ability a gift from the gods?

John Ruskin communicated his ideas so beautifully. About the making of a work of art he said, “Fine art is that in which the hand, the head, and the heart go together.”

Novelist George Eliot said about creation: “Great things are not done by impulse, but by a series of small things brought together.”

Creatives have a strong need for independence and resist having their work meddled with, as communicated by this quote from Patty McNair: “Get your mitts offa my story.”

The need for a developed expertise: “The repeated reminder of Mr. (Ezra) Pound: that poetry should be as well -written as prose” (T.S Eliot).

Eventually a writer will come to the conclusion that simplicity and naturalness are the keys to effective styles: “As for style in writing, if one has anything to say, it drops from him simply and directly” (Henry David Thoreau).

The best writing resists critical explanation: “In truly good writing no matter how many times you read it you do not know how it is done. That is because there is a mystery in all great writing and the mystery does not dissect out” (Ernest Hemingway).

The best writing resists critical explanation: “In truly good writing no matter how many times you read it you do not know how it is done. That is because there is a mystery in all great writing and the mystery does not dissect out” (Ernest Hemingway).

Inspirations are creative urges such as “Go ahead and do it”: “If you find a book you really want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it” (Toni Morrison).

The Work is Greater than the Artist Who Produced the Work

It is very common for people meeting someone who has produced a great work of art to be disappointed, not with the work, but with the impression the artist makes: “I thought he would be better looking” “He writes so beautifully but he’s not much of a conversationalist, is he?” Poet and essayist Joseph Brodsky said aptly, “What people can make with their hands is a lot better than they are themselves.”

© 2022 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click the following link:

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

or

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

or

As a really good writer, painter, actor, architect, or composer you have the ability to generate the best solutions to creative problems. The solutions are much better than the solutions less capable creatives settle on. Your aesthetic judgment is better than theirs. You perceive features of the problems facing you and the solutions to them that lesser creatives don’t notice and can’t think of.

As a really good writer, painter, actor, architect, or composer you have the ability to generate the best solutions to creative problems. The solutions are much better than the solutions less capable creatives settle on. Your aesthetic judgment is better than theirs. You perceive features of the problems facing you and the solutions to them that lesser creatives don’t notice and can’t think of. He had a staggering knowledge of American songs. I knew Marvin and would do exhaustive research trying to stump him with the least known and most esoteric songs my research could find, asking him “Who wrote…?” and “Who wrote…?” However obscure the song and no matter how confidently I thought, “He will never know this one,” he always knew.

He had a staggering knowledge of American songs. I knew Marvin and would do exhaustive research trying to stump him with the least known and most esoteric songs my research could find, asking him “Who wrote…?” and “Who wrote…?” However obscure the song and no matter how confidently I thought, “He will never know this one,” he always knew. Unlike ordinary writers who might not be aware that their plots are not believable, a really good writer would be aware if theirs were not. Yet, in spite of being vividly aware and quite objective and accurate about their own work, expert artists and writers have the weakness of often being wrong in their predictions about the performance of novices they have been asked to evaluate. It is as though they are unable to recognize talent while it is still in a formative state. In fact, the greater their expertise, the more likely they are to be wrong in predicting the performance of novices.

Unlike ordinary writers who might not be aware that their plots are not believable, a really good writer would be aware if theirs were not. Yet, in spite of being vividly aware and quite objective and accurate about their own work, expert artists and writers have the weakness of often being wrong in their predictions about the performance of novices they have been asked to evaluate. It is as though they are unable to recognize talent while it is still in a formative state. In fact, the greater their expertise, the more likely they are to be wrong in predicting the performance of novices. including the senior editor whose judgment was “always right” rejected it as impossible to understand. Only Charles Monteith, who had never edited a book before, argued angrily on behalf of the book he had fallen in love with despite its obvious flaws. Unlike the experts, he saw that good editing could remedy its weaknesses. Lord of the Flies, edited by Monteith, became an international best seller.

including the senior editor whose judgment was “always right” rejected it as impossible to understand. Only Charles Monteith, who had never edited a book before, argued angrily on behalf of the book he had fallen in love with despite its obvious flaws. Unlike the experts, he saw that good editing could remedy its weaknesses. Lord of the Flies, edited by Monteith, became an international best seller. Really good creatives are able to pull out of their minds–with ease–the insights they need. They are so able and accustomed to using the substantial skills they have developed, that they do so automatically, “without thought” as a Zen master would say. To them writing or painting is easy. Yet, at the same time, they may be victims of inflexibility in the face of new circumstances. At times they have trouble adjusting to situations confronting them.

Really good creatives are able to pull out of their minds–with ease–the insights they need. They are so able and accustomed to using the substantial skills they have developed, that they do so automatically, “without thought” as a Zen master would say. To them writing or painting is easy. Yet, at the same time, they may be victims of inflexibility in the face of new circumstances. At times they have trouble adjusting to situations confronting them. Really good creatives spend considerable time analyzing the problems facing them while less accomplished creatives spend less time and are not as patient as the exceptional creatives.

Really good creatives spend considerable time analyzing the problems facing them while less accomplished creatives spend less time and are not as patient as the exceptional creatives.  Genius in the arts or in any other pursuit is almost always specific to one art, one domain. Often it is assumed without too much thought that a person with a high level of skill in one area will almost automatically be skilled in another area or many other areas. That’s called “the halo effect.” Yet while there are exceptions, the halo effect is generally invalid. High-performing creators do not excel in areas where they have no expertise. But in a single domain they are on their home turf, and their work is really good.

Genius in the arts or in any other pursuit is almost always specific to one art, one domain. Often it is assumed without too much thought that a person with a high level of skill in one area will almost automatically be skilled in another area or many other areas. That’s called “the halo effect.” Yet while there are exceptions, the halo effect is generally invalid. High-performing creators do not excel in areas where they have no expertise. But in a single domain they are on their home turf, and their work is really good.

If you want to be successful in the arts, be older rather than younger. Older is better because most outstanding contributions to the arts are not made by people in their teens, 20s, 30s, or 40s, but in their 50s, 60s, and 70s. Why is that so? The main reason why, artistically, older is better than younger is that to have the ability to do artistic work expertly and do increasingly superior work, the main factor is the artist’s KNOWLEDGE and its PRACTICAL APPLICATION over a period of time that is often long.

If you want to be successful in the arts, be older rather than younger. Older is better because most outstanding contributions to the arts are not made by people in their teens, 20s, 30s, or 40s, but in their 50s, 60s, and 70s. Why is that so? The main reason why, artistically, older is better than younger is that to have the ability to do artistic work expertly and do increasingly superior work, the main factor is the artist’s KNOWLEDGE and its PRACTICAL APPLICATION over a period of time that is often long. No artist has ever lived –Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Proust, Picasso, Mozart–who had so much talent that they didn’t need considerable knowledge to excel at a high level. Talent is a blessing, but talent alone isn’t enough.

No artist has ever lived –Shakespeare, Michelangelo, Proust, Picasso, Mozart–who had so much talent that they didn’t need considerable knowledge to excel at a high level. Talent is a blessing, but talent alone isn’t enough. In any field in which you are intensely engaged, such as serious writing or painting, the brain you feed with knowledge just goes on learning and learning and learning and your abilities grow and grow. The more knowledge you have, the faster you’ll recognize related information that’s relevant to solving problems you are facing. You’ll be able to say, quite quickly, “So-and-so handled the problem I’m now facing by…” Acquiring knowledge is what you are doing all the time you’re working at your craft, talking with others about your craft, studying it, taking classes, reading, and practicing to develop your skills.

In any field in which you are intensely engaged, such as serious writing or painting, the brain you feed with knowledge just goes on learning and learning and learning and your abilities grow and grow. The more knowledge you have, the faster you’ll recognize related information that’s relevant to solving problems you are facing. You’ll be able to say, quite quickly, “So-and-so handled the problem I’m now facing by…” Acquiring knowledge is what you are doing all the time you’re working at your craft, talking with others about your craft, studying it, taking classes, reading, and practicing to develop your skills. The more knowledge that is needed to excel in a field, the more

The more knowledge that is needed to excel in a field, the more  Following in the footsteps of the greats is a vital route to writing knowledge, and knowledge leads to skills, and skills coupled with confidence lead to success. What helps is an aptitude for learning and learning fast, which I can hardly imagine a person in the arts not possessing.

Following in the footsteps of the greats is a vital route to writing knowledge, and knowledge leads to skills, and skills coupled with confidence lead to success. What helps is an aptitude for learning and learning fast, which I can hardly imagine a person in the arts not possessing. Let’s hope that your mind is a sponge sopping up knowledge because people in the arts who can acquire knowledge quickly and remember large amounts of it have an advantage when trying to create something original.

Let’s hope that your mind is a sponge sopping up knowledge because people in the arts who can acquire knowledge quickly and remember large amounts of it have an advantage when trying to create something original. fix. I was writing what should be an easy section on planning what you are about to write or paint. Now planning is something I know a lot about. For years I was a trainer for a consulting company I founded. I trained thousands of people to use the best techniques of planning so they might effectively plan whatever business or career project they had in mind.

fix. I was writing what should be an easy section on planning what you are about to write or paint. Now planning is something I know a lot about. For years I was a trainer for a consulting company I founded. I trained thousands of people to use the best techniques of planning so they might effectively plan whatever business or career project they had in mind. Even as children girls and boys who will become writers and painters when they grow up have been told and taught by teachers to plan the work before they begin to execute it. They are taught that in grade school, and in graduate school professors or experienced visiting artists and writers stipulate that every work should have a plan. Planning becomes a habit that isn’t questioned because “everyone knows you have to have a plan before you begin. How else will you know how to proceed?”

Even as children girls and boys who will become writers and painters when they grow up have been told and taught by teachers to plan the work before they begin to execute it. They are taught that in grade school, and in graduate school professors or experienced visiting artists and writers stipulate that every work should have a plan. Planning becomes a habit that isn’t questioned because “everyone knows you have to have a plan before you begin. How else will you know how to proceed?” Some creatives meticulously plan and think the work to be produced through to the last detail. But some non-planner creatives begin to paint or write without a subject in mind, preferring to permit the work to grow organically and emerge. Some writers, like me, begin without any conscious concept of how to proceed other than, at best, a notion not at all well-developed of what the work should probably be about.

Some creatives meticulously plan and think the work to be produced through to the last detail. But some non-planner creatives begin to paint or write without a subject in mind, preferring to permit the work to grow organically and emerge. Some writers, like me, begin without any conscious concept of how to proceed other than, at best, a notion not at all well-developed of what the work should probably be about. Non-planning Virginia Woolf said that her idea for Mrs. Dalloway started without any conscious direction. She thought of making a plan but soon abandoned the idea. She said, “The Book grew day by day, by week, without any plan at all, except that which was dictated each morning in the act of writing.” Had someone asked her what exactly she was trying to accomplish other than to follow a woman throughout a day she would have replied, “I’m not sure.” The planner- writers are sure of where they are going. Their plan tells them.

Non-planning Virginia Woolf said that her idea for Mrs. Dalloway started without any conscious direction. She thought of making a plan but soon abandoned the idea. She said, “The Book grew day by day, by week, without any plan at all, except that which was dictated each morning in the act of writing.” Had someone asked her what exactly she was trying to accomplish other than to follow a woman throughout a day she would have replied, “I’m not sure.” The planner- writers are sure of where they are going. Their plan tells them. The more spontaneous process which non-planning creatives like greats Woolf and Mark Twain (possibly America’s greatest writer) and Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci use to complete a work is contrary to the rational goal-setting, plan-making processes. Following a plan inhibits certain creatives for whom a more spontaneous approach results in better work.

The more spontaneous process which non-planning creatives like greats Woolf and Mark Twain (possibly America’s greatest writer) and Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci use to complete a work is contrary to the rational goal-setting, plan-making processes. Following a plan inhibits certain creatives for whom a more spontaneous approach results in better work. Galenson describes two significantly different types of artists. The “everything must be planned” artists are called Conceptualizers: they must have a full-blown concept of the work they wish to create in all its detail before they begin writing or painting the work. Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, James Joyce, Herman Melville, and F. Scott Fitzgerald were Conceptual writers. Pablo Picasso was a Conceptual painter. Conceptualizers state their carefully- wrought goals for a particular work precisely

Galenson describes two significantly different types of artists. The “everything must be planned” artists are called Conceptualizers: they must have a full-blown concept of the work they wish to create in all its detail before they begin writing or painting the work. Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, James Joyce, Herman Melville, and F. Scott Fitzgerald were Conceptual writers. Pablo Picasso was a Conceptual painter. Conceptualizers state their carefully- wrought goals for a particular work precisely  Once Conceptualizers find the crucial problem they advance slowly with a plan, but Experimentalists move fast without a plan. Experimentalist’s goals are imprecise. They have ideas about what the work will be like when it is finished, but are unclear about everything else until the piece is written, the painting mounted on a wall. That imprecision is how Experimentalists like to work, but it creates problems. Not clear as to what they want the final work to look like, they have trouble finishing works.

Once Conceptualizers find the crucial problem they advance slowly with a plan, but Experimentalists move fast without a plan. Experimentalist’s goals are imprecise. They have ideas about what the work will be like when it is finished, but are unclear about everything else until the piece is written, the painting mounted on a wall. That imprecision is how Experimentalists like to work, but it creates problems. Not clear as to what they want the final work to look like, they have trouble finishing works. Conceptualizers tend to bloom early, often with a striking new style or innovation or great success at the start of their career. They mature quickly, starting very early, not gradually through years of trial and error as Experimentalist painters like Jackson Pollock and Claude Monet did, but rapidly. A young Ernest

Conceptualizers tend to bloom early, often with a striking new style or innovation or great success at the start of their career. They mature quickly, starting very early, not gradually through years of trial and error as Experimentalist painters like Jackson Pollock and Claude Monet did, but rapidly. A young Ernest  People in every walk of life and in every hemisphere on earth–in cities, on deserts, in towns and villages–long to create something. My nine year old grandson is a talented artist and cellist studying architecture. His six year old sister takes dance and will begin taking piano lessons in the fall. Their forty two year old father was an excellent cellist in his youth and was inspired by the performance of a famous cellist to return to it last year. My wife, is a former cellist, and has taken up water colors and has returned to the piano. I write every day. I have for many years, and when I am not writing I am thinking about it and planning what I will write. We are representative people no different from millions of others with whom we share the globe because the current era is an Age of Heightened Creativity. Little children and women and men of all ages are bent on having creative experiences. They will not let their creative instincts be stifled.

People in every walk of life and in every hemisphere on earth–in cities, on deserts, in towns and villages–long to create something. My nine year old grandson is a talented artist and cellist studying architecture. His six year old sister takes dance and will begin taking piano lessons in the fall. Their forty two year old father was an excellent cellist in his youth and was inspired by the performance of a famous cellist to return to it last year. My wife, is a former cellist, and has taken up water colors and has returned to the piano. I write every day. I have for many years, and when I am not writing I am thinking about it and planning what I will write. We are representative people no different from millions of others with whom we share the globe because the current era is an Age of Heightened Creativity. Little children and women and men of all ages are bent on having creative experiences. They will not let their creative instincts be stifled. It became a permanent part of your entire being–an idea, a theme, or an image that became a guiding force in your life. You may not be conscious of it, but it starts you out in a creative direction, and gives you a sense of moving steadily in that direction, of heading straight toward something concrete and specific. Making a living in art is difficult and so most artists must find financial security other than in art. But whatever your occupation if you are to be an artist you will define yourself first as an artist, an accountant, HR manger, or English teacher second.

It became a permanent part of your entire being–an idea, a theme, or an image that became a guiding force in your life. You may not be conscious of it, but it starts you out in a creative direction, and gives you a sense of moving steadily in that direction, of heading straight toward something concrete and specific. Making a living in art is difficult and so most artists must find financial security other than in art. But whatever your occupation if you are to be an artist you will define yourself first as an artist, an accountant, HR manger, or English teacher second. Noted composers and performing artists in musical fields–so sensitive to sound and tone—possess what the Germans call Horlust–“hearing passion.” Writers–particularly poets and lyrical writers–have a word passion (they adore words), and painters adore colors and shapes, often from the cradle.

Noted composers and performing artists in musical fields–so sensitive to sound and tone—possess what the Germans call Horlust–“hearing passion.” Writers–particularly poets and lyrical writers–have a word passion (they adore words), and painters adore colors and shapes, often from the cradle. What is inside the shut door is the artist’s rich inner life from which creative products pour–without stopping if the artists explore themselves more and more deeply. Transformation of what is inside the artist into what is outside is the

What is inside the shut door is the artist’s rich inner life from which creative products pour–without stopping if the artists explore themselves more and more deeply. Transformation of what is inside the artist into what is outside is the  Poet W.H. Auden wrote, “Speaking for myself, the questions which interest me most when reading a poem are two. The first is technical: ‘Here is the verbal contraption. How does it work?’ The second is, in the broadest sense moral. What kind of guy inhabits this poem? What is his notion of the good life or the good place? His notion of the Evil One. What does he conceal from the reader? What does he conceal even from himself?” William James said it is the amount of life in the act of creation which artists feel that makes you value their mind.

Poet W.H. Auden wrote, “Speaking for myself, the questions which interest me most when reading a poem are two. The first is technical: ‘Here is the verbal contraption. How does it work?’ The second is, in the broadest sense moral. What kind of guy inhabits this poem? What is his notion of the good life or the good place? His notion of the Evil One. What does he conceal from the reader? What does he conceal even from himself?” William James said it is the amount of life in the act of creation which artists feel that makes you value their mind. Artists must be people of action because their main goal is production of works over which they think and

Artists must be people of action because their main goal is production of works over which they think and  Children and adults may drop out, but those who turn to art may well be playing the cello or dancing or painting, only getting better and enjoying their art perpetually–all their lives– with fond

Children and adults may drop out, but those who turn to art may well be playing the cello or dancing or painting, only getting better and enjoying their art perpetually–all their lives– with fond  Although talent in the arts most often shows itself early, because it takes so many years to develop their talent and become highly proficient in the arts, people who will become expert musicians, painters, performers, and writers can expect to be late bloomers. Artists who perform at a high level do not demonstrate remarkable talent in short order. They are not usually in their twenties or thirties, but in their forties, fifties, and sixties. All spend many years developing the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that will eventually enable them to be recognized for their mastery. All arts involve learning form and the art’s devices, and the need for control, craft, revisions, and structure–time consuming efforts. All begin by imitating existing techniques they have studied.

Although talent in the arts most often shows itself early, because it takes so many years to develop their talent and become highly proficient in the arts, people who will become expert musicians, painters, performers, and writers can expect to be late bloomers. Artists who perform at a high level do not demonstrate remarkable talent in short order. They are not usually in their twenties or thirties, but in their forties, fifties, and sixties. All spend many years developing the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that will eventually enable them to be recognized for their mastery. All arts involve learning form and the art’s devices, and the need for control, craft, revisions, and structure–time consuming efforts. All begin by imitating existing techniques they have studied. A survey of 47 outstanding instrumentalists found that their ability was first noticed on average at the age of four years and nine months. Then they began a very long and arduous period of development of their talent. Pianists work for about seventeen years from their first formal lessons to their first international recognition, involving many thousands of hours of intense practice. The fastest in one study was twelve years, and the slowest took twenty-five years. In other fields you may even be an early bloomer, but in the arts if your expertise is to be at a high level of mastery, unless you are a Dylan Thomas, a rarity who was at his peak at nineteen, you had best avoid discouragement and expect to bloom late.

A survey of 47 outstanding instrumentalists found that their ability was first noticed on average at the age of four years and nine months. Then they began a very long and arduous period of development of their talent. Pianists work for about seventeen years from their first formal lessons to their first international recognition, involving many thousands of hours of intense practice. The fastest in one study was twelve years, and the slowest took twenty-five years. In other fields you may even be an early bloomer, but in the arts if your expertise is to be at a high level of mastery, unless you are a Dylan Thomas, a rarity who was at his peak at nineteen, you had best avoid discouragement and expect to bloom late. Novelist

Novelist  When the majority of their friends and associates are settled in a career and life style, late bloomers are not. Late bloomers may eventually reach the height of their achievements and fulfillment which I call “their true

When the majority of their friends and associates are settled in a career and life style, late bloomers are not. Late bloomers may eventually reach the height of their achievements and fulfillment which I call “their true  If you’re a late bloomer, you’ve made false starts. You haven’t peaked yet, haven’t reached your destiny yet, but you may be determined to bloom one day. Late bloomers are more willing than most to persevere and if need be to fail but try again and again until they reach a life they desire. If you are a late bloomer, more than most people you have the sense that you’re constructing yourself as you go along, even rejecting what other people may call golden opportunities if those opportunities don’t appear to lead you in the direction you desire most.

If you’re a late bloomer, you’ve made false starts. You haven’t peaked yet, haven’t reached your destiny yet, but you may be determined to bloom one day. Late bloomers are more willing than most to persevere and if need be to fail but try again and again until they reach a life they desire. If you are a late bloomer, more than most people you have the sense that you’re constructing yourself as you go along, even rejecting what other people may call golden opportunities if those opportunities don’t appear to lead you in the direction you desire most. with the goal in mind for me to have a national television talk show. It was an excellent opportunity and would have paid extremely well. But my wife and I talked it over and I decided that what I wanted to do with my life above all else was simply to sit at a computer in my upstairs work room while my four children played noisily downstairs and my wife came up once in a while to say hello, and produce artful paragraphs that reflected my years of hard work and training. To me that was blooming. I turned the opportunity down. Late bloomers often make similar very difficult decisions while they are constructing themselves.

with the goal in mind for me to have a national television talk show. It was an excellent opportunity and would have paid extremely well. But my wife and I talked it over and I decided that what I wanted to do with my life above all else was simply to sit at a computer in my upstairs work room while my four children played noisily downstairs and my wife came up once in a while to say hello, and produce artful paragraphs that reflected my years of hard work and training. To me that was blooming. I turned the opportunity down. Late bloomers often make similar very difficult decisions while they are constructing themselves. Most people–possibly all–who find fulfillment later in life find it in a mission, calling, or vocation. You cannot be dissatisfied when you’re doing the work for which you feel you were brought into the world, a thought that consoled

Most people–possibly all–who find fulfillment later in life find it in a mission, calling, or vocation. You cannot be dissatisfied when you’re doing the work for which you feel you were brought into the world, a thought that consoled  Going back to school as a transition to another field is a strategy late bloomers find appealing, in essence ending one career and starting another.

Going back to school as a transition to another field is a strategy late bloomers find appealing, in essence ending one career and starting another. Have you bloomed? If you haven’t what are you going to do about that? People who aren’t leading satisfactory lives haven’t bloomed at all, and many are trying to, but many have never started trying, and just as many have given up. Better to start if you haven’t already, whatever your age or condition in life. You can always forget the past and start out again, making no excuses for starting out late. Experiment, follow your instincts, and assess yourself and your feelings about your life. Are you going right or are you going wrong?

Have you bloomed? If you haven’t what are you going to do about that? People who aren’t leading satisfactory lives haven’t bloomed at all, and many are trying to, but many have never started trying, and just as many have given up. Better to start if you haven’t already, whatever your age or condition in life. You can always forget the past and start out again, making no excuses for starting out late. Experiment, follow your instincts, and assess yourself and your feelings about your life. Are you going right or are you going wrong? thousands of hours developing yours (so that I’d recognize anywhere that it is yours), I have consciously spent many hours developing mine.

thousands of hours developing yours (so that I’d recognize anywhere that it is yours), I have consciously spent many hours developing mine.

changing or ineffable in a single sentence, you face both the limitations of the sentence itself and the extent of your own talent” (Pat Conroy).

changing or ineffable in a single sentence, you face both the limitations of the sentence itself and the extent of your own talent” (Pat Conroy). finishing, you’ve developed a bad habit and you’d better do something about it.

finishing, you’ve developed a bad habit and you’d better do something about it. start another contrary, more fruitful habit. To break the habit of consistently not writing, you develop the habit of writing regularly. To combat the habit of quitting too soon, you make yourself not quit.

start another contrary, more fruitful habit. To break the habit of consistently not writing, you develop the habit of writing regularly. To combat the habit of quitting too soon, you make yourself not quit. You’re not a child or hedonist, a worshipper of permissiveness and pleasure who doesn’t have any will power. There are many writers who write not the traditional four or fewer hours daily, but put in eight hours a day, much longer than the majority, considering themselves no different than their parents who worked eight hours a day and the majority of the work force who work eight hours daily.

You’re not a child or hedonist, a worshipper of permissiveness and pleasure who doesn’t have any will power. There are many writers who write not the traditional four or fewer hours daily, but put in eight hours a day, much longer than the majority, considering themselves no different than their parents who worked eight hours a day and the majority of the work force who work eight hours daily. It takes longer to completely absorb yourself in an ambitious project than in an easier, less complicated one. And during that period, distractions seem to come up out of the ground. Any intrusion on the delicate world of a creative mind can make that world disappear. Every intrusion not only robs you of time, but also of the time it takes you to recover. If you set a goal of working a three-hour session and have three interruptions you may be busy for three hours but only do fifteen minutes of actual work. If you try to do four things simultaneously, you’ll probably only finish one, at most two.

It takes longer to completely absorb yourself in an ambitious project than in an easier, less complicated one. And during that period, distractions seem to come up out of the ground. Any intrusion on the delicate world of a creative mind can make that world disappear. Every intrusion not only robs you of time, but also of the time it takes you to recover. If you set a goal of working a three-hour session and have three interruptions you may be busy for three hours but only do fifteen minutes of actual work. If you try to do four things simultaneously, you’ll probably only finish one, at most two. Don’t let a

Don’t let a  work that leads to the fulfillment of your gifts over the avoidance of work.

work that leads to the fulfillment of your gifts over the avoidance of work. Actor Lord Laurence Olivier aimed at perfect performances, as did Peter O’Toole, Olivier’s successor as the world’s greatest actor–the perfect performances in the perfect tragedies as the perfect characters–as Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, or Iago. One night Olivier felt that he had achieved perfection in a performance. Others in the cast also told him he had. He said, “What I’m thinking is I’ve done it, but will I be able to do it again?” Perfection is difficult and rare. It is hard to repeat. It is a concept that grows in importance to artists as their skills and accomplishments ascend to high levels.

Actor Lord Laurence Olivier aimed at perfect performances, as did Peter O’Toole, Olivier’s successor as the world’s greatest actor–the perfect performances in the perfect tragedies as the perfect characters–as Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, or Iago. One night Olivier felt that he had achieved perfection in a performance. Others in the cast also told him he had. He said, “What I’m thinking is I’ve done it, but will I be able to do it again?” Perfection is difficult and rare. It is hard to repeat. It is a concept that grows in importance to artists as their skills and accomplishments ascend to high levels. It is true that serious dancers currently and throughout history have aimed at perfection, but other artists–usually the best in the art, those that are aware that they have a significant talent–also aim for perfection in their work, I believe. Those who do aim for perfection in their novels, musical composition, and paintings and other art works let it be known through their

It is true that serious dancers currently and throughout history have aimed at perfection, but other artists–usually the best in the art, those that are aware that they have a significant talent–also aim for perfection in their work, I believe. Those who do aim for perfection in their novels, musical composition, and paintings and other art works let it be known through their  When they are watching the performance of a play what the audience hopes to see more than anything else is a virtuoso performance they will not be able to forget however long they live and how many plays they see. The virtuoso performance is the single most exciting and popular feature not only of drama but of any art, and the most thrilling feature of a virtuoso performance is not the possibility that the artist may fail. Rather, it is the spectacle of succeeding in an extraordinary way–a performance that is perfect because it has no errors. All the time I am listening to music as I do all day long or reading a narrative I think is great such as James Joyce’s short story “Araby,” and Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning” I am thinking, “Keep it up James and Frank. Don’t fail. Continue being great until the story or the song is finished and perfect from the beginning to the end”

When they are watching the performance of a play what the audience hopes to see more than anything else is a virtuoso performance they will not be able to forget however long they live and how many plays they see. The virtuoso performance is the single most exciting and popular feature not only of drama but of any art, and the most thrilling feature of a virtuoso performance is not the possibility that the artist may fail. Rather, it is the spectacle of succeeding in an extraordinary way–a performance that is perfect because it has no errors. All the time I am listening to music as I do all day long or reading a narrative I think is great such as James Joyce’s short story “Araby,” and Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning” I am thinking, “Keep it up James and Frank. Don’t fail. Continue being great until the story or the song is finished and perfect from the beginning to the end” The days and nights of everyday living of the artist seeking perfection must be filled to the brim with their art. More than likely, the artist has grown up with it, seen it mature, and watched it take over a good part of his or her being. Short story master Raymond Carver reflecting on his career put it this way: “conversation was fine, camaraderie was fine, making love was fine, raising a family was okay, but interfered with writing.”

The days and nights of everyday living of the artist seeking perfection must be filled to the brim with their art. More than likely, the artist has grown up with it, seen it mature, and watched it take over a good part of his or her being. Short story master Raymond Carver reflecting on his career put it this way: “conversation was fine, camaraderie was fine, making love was fine, raising a family was okay, but interfered with writing.”

Why what I’m going to say now is true, no one has been able to figure out, but almost all people relax their efforts when they get close to achieving even their most important goals. They struggle and struggle and then seem to get lazy and disinterested. They are like a sprinter who runs fast to the tape and slows down or stops. But good coaches advise runners to “run through the tape.” Whatever you do, don’t relax just when you’re getting close to success, but persist in applying your utmost energy

Why what I’m going to say now is true, no one has been able to figure out, but almost all people relax their efforts when they get close to achieving even their most important goals. They struggle and struggle and then seem to get lazy and disinterested. They are like a sprinter who runs fast to the tape and slows down or stops. But good coaches advise runners to “run through the tape.” Whatever you do, don’t relax just when you’re getting close to success, but persist in applying your utmost energy Why are you and I so afraid of failure? Many people live in terror of it and feel they must never fail, but always succeed, trailing clouds of glory. Yet failure can be a blessed life-changing event. If you experience only successes, you come to expect quick and easy results, and your sense of confidence is easily undermined if you suffer a setback. Setbacks and failures serve two useful purposes: Not only do they show us that we need to make changes and adjustments in order to gain the success we are seeking, but also they teach us that success usually requires confident, persistent, skilled, focused effort sustained over time. Once you set failures aside and become convinced that you have what it takes to succeed, you quickly rebound from failures. By having courage and sticking it out through tough times, you come out on the far side of failures with even greater confidence and commitment.

Why are you and I so afraid of failure? Many people live in terror of it and feel they must never fail, but always succeed, trailing clouds of glory. Yet failure can be a blessed life-changing event. If you experience only successes, you come to expect quick and easy results, and your sense of confidence is easily undermined if you suffer a setback. Setbacks and failures serve two useful purposes: Not only do they show us that we need to make changes and adjustments in order to gain the success we are seeking, but also they teach us that success usually requires confident, persistent, skilled, focused effort sustained over time. Once you set failures aside and become convinced that you have what it takes to succeed, you quickly rebound from failures. By having courage and sticking it out through tough times, you come out on the far side of failures with even greater confidence and commitment. The effect of

The effect of  Confidence is needed if you are to be successful as an artist. Make it a point to never lose confidence. If you find yourself losing it, use affirming statements, such as “I can do this; I believe in myself.’

Confidence is needed if you are to be successful as an artist. Make it a point to never lose confidence. If you find yourself losing it, use affirming statements, such as “I can do this; I believe in myself.’ The most successful people have high career aspirations, are confident, and generally attribute their success to high effort and failure to lack of effort.

The most successful people have high career aspirations, are confident, and generally attribute their success to high effort and failure to lack of effort. Creative people who are the most likely to ask for help are those with a high opinion of themselves, while those with a low opinion of themselves are the least likely, although they may be the most in need of it and would profit from it. Asking for help shows that you’re serious about reaching your goals. Useful feedback can help you evolve and reach high levels of satisfaction and achievement.

Creative people who are the most likely to ask for help are those with a high opinion of themselves, while those with a low opinion of themselves are the least likely, although they may be the most in need of it and would profit from it. Asking for help shows that you’re serious about reaching your goals. Useful feedback can help you evolve and reach high levels of satisfaction and achievement.