Fjord, Norway by Pamela Jones

Some creatives have an ability to perceive images in their environment or deep in their memories and to elaborate them in works with astonishing dexterity. Simple images that are ready for practical artistic use in poems, novels, essays, short stories, and paintings and such pour in unabated rivers from their minds. Skill in image-making comes so effortlessly to superb image-makers that although their ability is exceptional, it seems routine and unexceptional to them. If one image would do the trick, they can easily think of three, four, or five others that would suffice as well.

Skill with images is so necessary to the professional or professional-caliber amateur that if it is a weakness, it must be practiced and made a strength. That is possible to do.

Tenby Harbour Pembrokeshire West Wales by Pamela Jones

Creatives differ in the vividness of the imagery in their minds and in their ability to transform imagery. Compared with low imagers, vivid imagers experience large mental images of greater clarity, remember pictures better, and read text more slowly, presumably because they are visualizing as they read. Skill with imagery is a collection of identifiable abilities such as moving and rotating mages and inspecting them. Vivid imagers are able to hold in mind many features of an image at the same time. People can be good at one or more of these abilities, but poor at others.

POETRY OF IMAGISTS

William Carlos Williams

(Excerpt from “Nantucket”)

Flowers through the window

lavender and yellow

changed by white curtains–

Smell of cleanliness–

Sunshine of late afternoon–

On the glass tray

a glass pitcher, the tumbler

turned down

Stroll in the Moonlight Mumbles by Pamela Jones

For image-makers, remembering images and turning them into artistic products is a necessary part of their everyday approach to their work and a gift granted to many artists that surpasses the abilities of the overwhelming majority of people. In a single glance artists with a facility with images encounter a world of pictures, sounds, sensations, and odors that are their raw material.

An Imagist Poet:

“Evening” by Richard Aldington:

The chimneys, rank on rank,

Cut the clear sky;

The moon

With a rag of gauze about her loins

Poses among them, an awkward Venus–

And here am I looking wantonly

Over the kitchen sink.

Poems written in a strict imagist style are spare, elegant, and vivid. They are different from most poetry in that the reader isn’t expected to analyze them or search for symbols in them or explicate them. The imagist poem must be rooted in the ground of reality–must grow from the local and particular, and raise those to the universal, so when looking at some apparently small object one feels the swirl of significant events.

Cottage, Carmarthenshire, with Poppies by Pamela Jones

There is a juxtaposition of accumulated fragments. The poems require alertness enough mainly to “see” in your mind and don’t require explanation. One can’t explain a bead of water on a leaf, but it can be described, its beauty or mystery captured in words just as a painter captures them in pigment or the composer in notes and chords. Readers will enjoy them better if the poet or writer shuts up and just describes. The poems are complete as they are and need no interpretation. The physical and tangible qualities of the object–colors, shapes, odors, sensations–are identified one by one simply and precisely.

In the poetry of images the reader should not expect lofty sentiments. The poems do not have a regular beat and usually lack end-rhymes. Their language is vivid–plain, and direct. They calmly describe the scene and the object. They describe them precisely and exactly. Their imagery is compelling. Readers run their eyes along the scene. The poems focus on a short, specific period of time, are free verse, and often have a short poetic line such as my “Morning Glories:”

Sitting on a window sill

Watching people

Exchanging stories

Over white and purple

Morning glories

On the flanks of the hill

The poetry and prose of images emphasize verbs, not adjectives. The writing is clear, not obscure, and it is colloquial. Images are juxtaposed, one after another. They purposely stay on the surface of things, presenting details with no comments. If there are any ideas, they are left alone to take care of themselves. The writer or poet doesn’t reflect on them. The writing is not lofty or pretentious. The poet or writer takes obvious pleasure in words like the painter’s pleasure in using a brush.

THE VALUE OF MEMORY AND DETAIL

Hillside Cottage, Snowdonia, Snowdon, North Wales by Pamela Jones

There is an art underlying all the arts, and that is the art of memory and detail. The writing of the best writers and paintings of the best painters is full of details they recall–detailed images, detailed descriptions. They needn’t be long, but there must be memorable details if the work is to be convincing. The goal of a writer is to generate in the audience the sense that what the audiece is reading or hearing really happened, or is happening now, or might have happened in “real life.”

Content that is general and not vivid has little real-life effect on audiences or readers. Content like that isn’t convincing and is a misuse of words. But content that is not general, but specific, detailed, clear, unambiguous, truthful, and potent animates the readers’ minds and lets them know that a real person with an active mind and good memory of real things is talking to them.

I think if it were possible to analyze the brains of imagistic artists, poets, and writers, it would be found that the ability to recall the smallest and sometimes the most insignificant detail of lived experience–however long ago it occurred–is a major strength of a fine artist of any kind. A multiplicity of details must be put into the creative performance when art is to be done beautifully. A preciseness of vision is a necessity.

Details must be strategically placed in a written text so that they have maximum dramatic impact.

KEEP A NOTEBOOK OF IMAGES

A good practice if you want to animate your writing with images is to keep notebooks of images that come to mind and that you might one day put to use in writing or art. Here is a sample from one of my notebooks that contain thousands of images:

SUMMER: The warm summer rain pours through the sunlight. At night a fog floats in from the lake and slithers along the ground (like a snake.)… The report of fire crackers and booms of exploding rockets begin at nine: Independence Day… The orange and blues of the sunset were so beautiful at night that it was hard to believe they weren‘t painted…With every gust of wind the butterfly I’m watching is blown to another flower. ..It was morning. Here comes (came) the sun, warming every tree, every leaf, every pebble in the street… …waves scattering like broken glass,

Farmhouse in the Brecon Beacons Wales by Pamela Jones

SPRING: A band of squirrels climbs the trees …Whiter than snow and clearer than daylight was the night when the lightning flashed… Sparrows, blue jays, warblers and humming birds enjoyed themselves on the bushes, in the trees, in the sky. It had been a long day for them, but they seemed contented leading birds’ busy lives. Flowers seemed happy being flowers too. Two chipmunks sat aloof in the grass…The gutter leaked and a small waterfall poured from it… Squirrels shoot up the trees like gray rockets, hop across the branches, come back and bound across the grass where hungry robins stretch worms out of the ground…

SOUNDS Birds calling and playing, winds wafting in trees, lawn mowers humming–commuter trains rumbling, car horns and truck horns, fire engines, dogs barking, people laughing, shouting and talking, footsteps sounding, church bells playing songs.

T.S. Eliot was not an Imagist, but was influenced by Imagism.

From Eliot’s “Preludes:”

The winter evening settles down

With smell of stakes in passageways.

Six o’clock.

The burnt-out ends of smoky days,

And now a gusty shower wraps

The grimy scraps

Of withered leaves about your feet

And newspapers from vacant lots

Farm in the Brecon Beacons with Cow Parsley by Pamela Jones

Some poems of poetry of images are about stillness and some are about motion. The language is colloquial and vivid. The images are fresh and the reader is intended to see and listen freshly. Poetry and prose of images are written by people with vivid sensibilities and are intended for readers with similar sensibilities.

These skilled writers are describing what is occurring during specific moments of life, and pay close attention to the surfaces of physical things, as does my poem “Waitress in a Café in Kayenta Arizona.”

Fingers like sausage links,

Face round as a tire,

Hips the breadth of a moving van,

Elaborate, beauty-shop hair,

HAIKU AND IMAGERY

Haiku are made up almost always and almost completely of visual images. The three greatest haikuists were Basho, Buson, and Issa. The meaning of a haiku, like that of an imagist poem, is direct, clear, and perfect without interpretation or reference to other things. The meaning of haiku, like that of the imagist, is unmistakable and complete,

A few stars

Are now to be seen–

And frogs are croaking. (Basho)

Ah, how glorious

The young leaves, the green leaves,

Glittering in the sunshine. (Basho)

Three Cliffs Bay, Gower South Wales by Pamela Jones

Haikuists keep their eyes steadily on the objects. There is great art in the selection of the facts presented, but no “coloring.” The incidents, situations, and details are chosen from common life. Haikus describe things in themselves, not as symbols of other things. Haikus show modesty, simplicity, lack of affectation, no striving for effect, no trying to impress, no showing off. The haikuist just writes the story or sketch as plainl and as true to the haikuist’s vision and to life as he or she can. There is gentleness, and using the eye in particular, distinctness of the individual thing. Directness is in everything, snow, sky, clouds, sun. Each thing is simple and true:

The harvest moon–

Mist from the mountain foot

Clouded patties” (Basho)

The haiku must express a new or newly perceived sensation, a sudden awareness of the meaning of some common human experience of nature or man. Importantly, it must above all things, not be explanatory, or contain a cause and effect. There are nothing beyond phenomena. They are not symbols of something beyond themselves.

Flowers and birds

There among them, my wild

Peach blossoms. (Buson)

PROSE AND IMAGISTIC WRITING

Imagistic, highly descriptive prose augments writing that might otherwise be bland and lifeless. No material is dull in the hands of an imagist. Such prose is not just added on to the text like a pretty trimming, but is crucial to the meaning, the “feel” of the writing, and its impact on the reader.

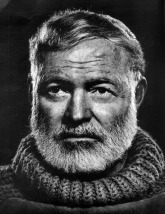

Ernest Hemingway from The Sun Also Rises:

“Before the waiter brought the sherry the rocket that announced the fiesta went up in the square. It burst and there was a gray ball of smoke high up above the Theatre Gayarre, across on the other side of the plaza. The ball of smoke hung in the sky like a shrapnel burst, and as I watched, another rocket came up to it, trickling smoke in the bright sunlight, I saw the bright flash as it burst and another little cloud of smoke appeared. By the time the second rocket had burst there were so many people in the arcade, that had been empty a minute before, that the waiter, holding the bottle high up over his head, could hardly get through the crowd to our table.”

From my “Wolves in the Rocky Mountains:”

“We sat at a table in the inn and ordered coffee. The utensils were gold. From the windows we watched through the falling snow eight stalking wolves winding down the mountain in single file, slowly, like liquid through the spruces and evergreens. It was getting late. We had stayed too long. We didn’t want to stay around until dark when at that elevation it would be really cold, and the wolves were on our mind. We paid and left on foot.

“Looking over our shoulders we saw the wolves streaking among the trees and circling and wheeling around and teasing and tormenting a young deer they had separated from a herd. We could hear the wolves and the deer breathing and see the wolves when they weren’t attacking the deer playfully burrowing their snouts in the snow. There was nothing we could do to save the deer. We didn’t want to watch.”

Starry Sky, Three Cliffs Bay, Gower by Pamela Jones

The prose and poems of images depend on the power of a clear perception of concrete–not abstract–things seen, heard, smelled, or touched by the creative to capture and hold readers’ attention and convey meaning. An imagistic writer’s, poet’s, and painter’s “eye” and “ear” in particular are capable of reproducing a sensual world they have experienced at some time in their lives and have not forgotten.

The artist whose work is featured in this post is Pamela Jones, a superb landscape artist who ives in West Cross Mumbles in Swansea, Wales. In her enchanting paintings, she is influenced by the beautiful scenery in Wales and the UK. She says, “I have a slightly impressionistic style, staying away from the photographic copying of a scene. I simplify what I see. I feel the artist must balance skill and imagination for there to be feeling in the painting. Colour harmony is most important. I give the impression of the place. I hope the viewer sees this when they look at my paintings.” She says that she just has to paint; it is a sort of obsession, and she paints every day.

© 2020 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click the following link:

Interview with David J. Rogers

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fighting-to-win-samurai-techniques-for-your-work-and-life-david-rogers/1119303640?ean=2940149174379

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

Click on book image to order from Amazon.com

or

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/waging-business-warfare-lessons-from-the-military-masters-in-achieving-competetive-superiority-revised-edition-david-rogers/1119079991?ean=2940149284030

Follow my blog with Bloglovin

Every memoirist, (as well as every writer of fiction and personal essays and every poet and playwright) should strive to make that attainable talent to evoke the past a part of their repertoire of skills. They can then call on that talent every day as they compose, and it will bring their writing vividly to life.

Every memoirist, (as well as every writer of fiction and personal essays and every poet and playwright) should strive to make that attainable talent to evoke the past a part of their repertoire of skills. They can then call on that talent every day as they compose, and it will bring their writing vividly to life. There were not enough living room chairs to go around when the full family came over, but there were the dining room chairs to carry in and also for an overflow crowd there were gray metal fold-up chairs stenciled on the back in white “Property of Ebenezer Baptist Church.” Aunt Sarah stored them in the hall closet hidden behind her prized full-length fur coat, and was embarrassed for strangers to see them, for fear they believe the impossible, but conceivable–that she had pilfered the chairs from that house of God.

There were not enough living room chairs to go around when the full family came over, but there were the dining room chairs to carry in and also for an overflow crowd there were gray metal fold-up chairs stenciled on the back in white “Property of Ebenezer Baptist Church.” Aunt Sarah stored them in the hall closet hidden behind her prized full-length fur coat, and was embarrassed for strangers to see them, for fear they believe the impossible, but conceivable–that she had pilfered the chairs from that house of God. On a kitchen wall, above the old serviceable stove, was fastened an Elgin clock that ran fast, forcing everyone to subtract twenty-two minutes a day if they wished for some reason to be accurate, and in the corner of the living room, close to the large drafty window fronting Austin Avenue, was an impressive century- old grandfather clock whose big bronze pendulum, to the entire family’s collective memory, had never moved.

On a kitchen wall, above the old serviceable stove, was fastened an Elgin clock that ran fast, forcing everyone to subtract twenty-two minutes a day if they wished for some reason to be accurate, and in the corner of the living room, close to the large drafty window fronting Austin Avenue, was an impressive century- old grandfather clock whose big bronze pendulum, to the entire family’s collective memory, had never moved.

The breathtaking Hawaiian Islands are an inappropriate place to become ill, but Honolulu, their state capital, largest city, and principal port, is where my younger sister Sharon had chosen to live–where the last months of her life she was hospitalized. In her early twenties she had left Chicago where we had grown up and I still live and she had visited one exquisite picture post card place after another in Spain, France, the South Pacific, and the Mediterranean, and so on, in search of the single place where she thought she would be happiest living and had found it.

The breathtaking Hawaiian Islands are an inappropriate place to become ill, but Honolulu, their state capital, largest city, and principal port, is where my younger sister Sharon had chosen to live–where the last months of her life she was hospitalized. In her early twenties she had left Chicago where we had grown up and I still live and she had visited one exquisite picture post card place after another in Spain, France, the South Pacific, and the Mediterranean, and so on, in search of the single place where she thought she would be happiest living and had found it. On the nights of my visit after seeing her I would walk on the beaches, reflecting on the day, finding restful the fresh air and coolness, and sleeping at Sharon and Ron’s apartment. On the kitchen floor there was a scale to measure the dwindling of my sister’s existence, and sheets of paper on a clipboard suspended from a nail on the wall that recorded her declining weight: ninety-eight pounds, ninety, eighty-eight…and a calendar that had Xs on days she wasn’t healthy enough to work that in recent months had become all Xs. Against a wall there was a full-length gold-framed mirror that in the past she had looked into. The mirror was dusty.

On the nights of my visit after seeing her I would walk on the beaches, reflecting on the day, finding restful the fresh air and coolness, and sleeping at Sharon and Ron’s apartment. On the kitchen floor there was a scale to measure the dwindling of my sister’s existence, and sheets of paper on a clipboard suspended from a nail on the wall that recorded her declining weight: ninety-eight pounds, ninety, eighty-eight…and a calendar that had Xs on days she wasn’t healthy enough to work that in recent months had become all Xs. Against a wall there was a full-length gold-framed mirror that in the past she had looked into. The mirror was dusty. There was no need for Kathy and me to discuss where Sharon stood. It needn’t be said that it wouldn’t be long and that soon Sharon would be gone entirely from my life and from the world. I knew that the moment coming from the airport and entering her hospital room and putting down my bag when I saw with a shock how puny Sharon looked now. The illness had given her an old woman’s body that had been ravaged by suffering there in that bed that was now her final home–so skinny–all bones–very sick–dying. The pain had turned her black hair white and it was short from the treatment and no longer long. Her once-pretty face was gaunt, her cheeks gray, her body very tired. Her long pianist’s fingers were so thin that her ring had slipped off and was lost. But there in her gray, lonely, fading beauty there was still about her that same gentleness you could ruffle with your breath, the same spirit in her fierce eyes, the same poise, and the same elegance. Looking into my eyes, imagining what I was seeing, Sharon had clutched her gown across her chest in embarrassment –covering herself in shame–still a modest woman–and said, breaking my heart, sucking the breath out of my lungs, “I’m a mess aren’t I?,” and I had replied to her, “Shar, you are beautiful.”

There was no need for Kathy and me to discuss where Sharon stood. It needn’t be said that it wouldn’t be long and that soon Sharon would be gone entirely from my life and from the world. I knew that the moment coming from the airport and entering her hospital room and putting down my bag when I saw with a shock how puny Sharon looked now. The illness had given her an old woman’s body that had been ravaged by suffering there in that bed that was now her final home–so skinny–all bones–very sick–dying. The pain had turned her black hair white and it was short from the treatment and no longer long. Her once-pretty face was gaunt, her cheeks gray, her body very tired. Her long pianist’s fingers were so thin that her ring had slipped off and was lost. But there in her gray, lonely, fading beauty there was still about her that same gentleness you could ruffle with your breath, the same spirit in her fierce eyes, the same poise, and the same elegance. Looking into my eyes, imagining what I was seeing, Sharon had clutched her gown across her chest in embarrassment –covering herself in shame–still a modest woman–and said, breaking my heart, sucking the breath out of my lungs, “I’m a mess aren’t I?,” and I had replied to her, “Shar, you are beautiful.” the happy girl and boy that we had once been, getting ready to ride our bikes to the library. The gray interior lights were dimmed low, as if the plane itself were drowsy. Everything was silent but for the deep hum of the engines, the other passengers asleep. I wanted to prepare myself for what it would be like now without a sister, my parents without a daughter, my children without an aunt.

the happy girl and boy that we had once been, getting ready to ride our bikes to the library. The gray interior lights were dimmed low, as if the plane itself were drowsy. Everything was silent but for the deep hum of the engines, the other passengers asleep. I wanted to prepare myself for what it would be like now without a sister, my parents without a daughter, my children without an aunt.

Writing vivid descriptions is a skill writers should strive to refine. Yet it is a weakness of many writers. If your ability to write effective descriptions is lacking it should be worked on vigorously and

Writing vivid descriptions is a skill writers should strive to refine. Yet it is a weakness of many writers. If your ability to write effective descriptions is lacking it should be worked on vigorously and  picked up. Into the air fluttered two hundred gulls with noisy wings. Above us clouds raced each other headlong across the coal black sky. Onto the shore crashed a procession of liquid walls–white-crested, angled slightly off to the south where blocks of limestone twenty feet high lay as if dropped from the heavens by gods. The magnificent waves rose–hills of water that seemed to pause, suspended for a moment at their peak as though they could rise no higher, and then crumbled and broke on the shore like a multitude of shattered stars. The spume spread and undertows slid back like shears below the breakers. Wave upon wave upon wave upon wave rose, lunged, and plunged like a field of gray-green wheat bowing under the wind. Just a moment before there had been not a breeze, not a breath of wind. But now all the wind in the world seemed to be concentrated on that strip of earth. It was a lion of a wind unleashed, untamed, cool, cold, with a sparkle, bite, and sting–many winds in fact, one gust coming, ending, another coming, another waiting–bringing pouring in to us the odors of water, of fish, and of the wind itself. The hoarse roar of the foaming waves filled all the air with the sounds of artillery. Trees on the shore bent as though made of rubber and our drenched bodies glistened.

picked up. Into the air fluttered two hundred gulls with noisy wings. Above us clouds raced each other headlong across the coal black sky. Onto the shore crashed a procession of liquid walls–white-crested, angled slightly off to the south where blocks of limestone twenty feet high lay as if dropped from the heavens by gods. The magnificent waves rose–hills of water that seemed to pause, suspended for a moment at their peak as though they could rise no higher, and then crumbled and broke on the shore like a multitude of shattered stars. The spume spread and undertows slid back like shears below the breakers. Wave upon wave upon wave upon wave rose, lunged, and plunged like a field of gray-green wheat bowing under the wind. Just a moment before there had been not a breeze, not a breath of wind. But now all the wind in the world seemed to be concentrated on that strip of earth. It was a lion of a wind unleashed, untamed, cool, cold, with a sparkle, bite, and sting–many winds in fact, one gust coming, ending, another coming, another waiting–bringing pouring in to us the odors of water, of fish, and of the wind itself. The hoarse roar of the foaming waves filled all the air with the sounds of artillery. Trees on the shore bent as though made of rubber and our drenched bodies glistened. “Young couples sitting on benches held each other, kissed, and heard the melancholy saxophone through the open windows of the gymnasium. Past a grove of gray trees, out on the lagoon, among mallards drifting on the water like leaves and bull frogs hidden in the shadows like thieves, students in row boats whose oars dangled free and made little splashing sounds, lay back, their bodies warm and glowing under light blankets. Contented, they were looked down upon by a pageantry of stars that seemed so close together that a finger wouldn’t fit between them. And while laughter floated like smoke through the night, they spoke of the incredible deeds they would one day perform.”

“Young couples sitting on benches held each other, kissed, and heard the melancholy saxophone through the open windows of the gymnasium. Past a grove of gray trees, out on the lagoon, among mallards drifting on the water like leaves and bull frogs hidden in the shadows like thieves, students in row boats whose oars dangled free and made little splashing sounds, lay back, their bodies warm and glowing under light blankets. Contented, they were looked down upon by a pageantry of stars that seemed so close together that a finger wouldn’t fit between them. And while laughter floated like smoke through the night, they spoke of the incredible deeds they would one day perform.” There was a tenderness and manly sweetness in my father’s manner, and too, the restraint of a gentlemanly politeness and natural shyness about speaking of things that moved him most profoundly, and which I knew indisputably he felt toward me, as I did toward him.

There was a tenderness and manly sweetness in my father’s manner, and too, the restraint of a gentlemanly politeness and natural shyness about speaking of things that moved him most profoundly, and which I knew indisputably he felt toward me, as I did toward him.