Writer Flannery O’Connor thought that any idiot with some talent can be taught to write a competent story, and something on that order may be true of all the arts. But a quest all creators aiming beyond mere competence are engaged in—writers, artists, actors, architects, dancers– or should be engaged in is discovering and refining a style which expresses exactly their unique vision and their unique skills and their unique selves.

When they settle on that style their work leaps up in quality and they are whole. But until they find it–it may take years– they cannot possibly come into their own and fully bloom and realize their highest creative potential. Style is the constant form in the creator’s work, the never-changing elements or qualities and expression of the person—his or her manner of communicating what is communicated.

When they settle on that style their work leaps up in quality and they are whole. But until they find it–it may take years– they cannot possibly come into their own and fully bloom and realize their highest creative potential. Style is the constant form in the creator’s work, the never-changing elements or qualities and expression of the person—his or her manner of communicating what is communicated.

Finding THE style that suits you supremely well is no small matter. A distinctive style that’s your own is the first sign of artistic greatness. There are styles that are okay for you and more styles that are wrong for you. And one style that is best. And the best may not be the style you’re writing in currently.

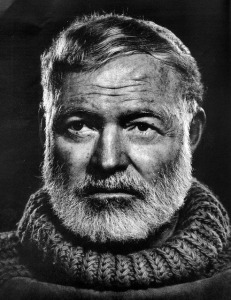

Nobel Prize winning writer Toni Morrison wrote that “getting a style is about all there is to writing fiction.” And the most influential literary stylist on earth in the last 100 years was American Ernest Hemingway whose Nobel Prize citation reads, “For his mastery of the art of narrative…and for the influence he has exerted on contemporary style.” Hemingway’s techniques “have profoundly influenced generations of writers across all boundaries of nationality, gender, race, ideology, sexual orientation, class, religion, and artistic temperament” (Robert Paul Lamb). Critic Alfred Kazin: Hemingway “gave a whole new dimension to English prose by making it almost as exact as poetry.” Joan Didion said about Hemingway’s style: “I mean they’re perfect sentences.”

Probably no fiction writer before or since worked so hard for so long or prepared so thoroughly to create a personal manner of writing that was so perfectly suited to the writing he wanted to do. If you’re looking for a model of how a writer should develop skills you can do no better than hard-working Hemingway.

Probably no fiction writer before or since worked so hard for so long or prepared so thoroughly to create a personal manner of writing that was so perfectly suited to the writing he wanted to do. If you’re looking for a model of how a writer should develop skills you can do no better than hard-working Hemingway.

“In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves” (First paragraph of A Farewell to Arms).

Until you perfect your own style and are satisfied with it, you may wish to pick out from the style of Ernest Hemingway whatever might be useful to you. If you want to improve your writing by learning from the master—and what serious writer wouldn’t–here are 20 practical tips on writing like a Nobel Prize winner:

* To cause the most powerful emotional responses in the reader always understate, never overstate. Don’t lay it on thick. Write prose that’s always less emotional than the events seem to call for. No emotional excess. Reject sentimentality. Hemingway doesn’t state characters’ emotional responses at all except in the simplest way. He might say the character “felt lousy” or felt “bad.” The more emotionally charged a situation, the more emotional restraint you should use in writing about it. And then the result will be emotionally powerful. Flannery O’ Connor said the fiction writer has to realize that he can’t create emotions with emotion. If you want the reader to feel pity, be somewhat cold. Write in a subdued, unemotional voice. Make your prose cool and dispassionate.

* Don’t make the reader aware of your style. When you’re reading Hemingway you’re reading an extraordinary style. But you’re unaware of it.

* Have an intense awareness of the world of the senses. No one renders the physical world with more vividness than Hemingway. His descriptions of mountains, hills, plains, and valleys are beautiful and unrivaled.

* Base your paragraphs on simple sequences—the Hemingway character does this, then does that, then does something else—gets up from the table, crosses the room, goes down the stairs, and then steps outside where the sun is shining and the flowers are red and yellow.

* Avoid describing the mental state of characters. Show it in the action.

* Simplify in every way you can. Willa Cather said, “The higher processes of art are all processes of simplification.” “To write simply is as difficult as to be good” (Somerset Maugham). Fiction these days has shifted more and more toward greater conciseness and simplicity.

* Be completely objective. The more objective you are the stronger will be the impression your writing will make on the reader. State the facts.

* Tell the truth. “A writer’s job is to tell the truth…Do not describe scenes you have not witnessed yourself” (Hemingway). Write down what you see and feel in the simplest way you can. Anton Chekhov: “One must never lie. Art has this great specification: it simply does not tolerate falsehood…there is absolutely no lying in art.” Hemingway’s works are generally autobiographical and stamped with authenticity. He never wrote about anything he hadn’t first experienced himself. He said, “I can only write from memory.” That creates trust in the reader.

* Show absolute sincerity. The particularly effective writer will develop a relationship with readers that goes beyond liking to intimacy, and that comes from above all else the sincerity the reader finds in the work. Hemingway is the sincerest of writers.

* Do no moralizing, no moral judgments—have no “messages.” Don’t preach.

* Eliminate long words or use them sparingly. But always use the mot just, the single best and most accurate word to convey exactly what you’re trying to say. “I have never used a word without first considering if it is replaceable” (Hemingway). Put the right words in the right order to do the subject the most justice.

* When writing short stories make the stories simple—simple plots. The more elaborate the plot of a short story, the less effective as a work of art it tends to be. In many Hemingway stories very little happens. In fact some of them aren’t even stories, but sketches that are only a few pages long. The same is true of Chekhov, and he and Hemingway, along with Guy de Maupassant, were the three greatest short story writers in the history of literature.

* Be brief, condensed, maximally concise. Not a single word should be unnecessary or superfluous. A minimum number of words selected with care.

* Provide few details and make them precise and concrete. Too much detail exhausts the readers and takes their mind off the action—and that’s where it should always be.

* Stress clarity at all times.

* It’s not necessary to state everything. Rely on suggestion. Leave some things for the reader to figure out.

* Write in a style that’s easy and flowing and has simple rhythms—a tremendously appealing sensual style.

* Keep sentences short and simple–a series of short declarative simple sentences, generally not complex or compound. No ornamental rhetoric. Write forceful and direct prose. There is hardly a single simile or metaphor in all the works of Hemingway. Dialogue sentences especially should be short.

* Severely limit adjectives and adverbs. Emphasize nouns and verbs. If Hemingway used adjectives they were inexact and common—“The trees were big and the foliage thick, but it was not gloomy.” The colors were “bright.” “Hemingway certainly helped bury the notion…that the more you pile on the adjectives the closer you get to describing the thing” (Tom Stoppard).

* Cut exposition to an absolute minimum. No explanations, discussion, analysis, and comments. Eliminate the frame. It’s not necessary. Jump right into the action.

Having found your right style you’ll be equipped to achieve the writer’s objective “to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader” (Hemingway). Everything with brevity, economy, simplicity, intensity. It isn’t possible to overstate the influence of Hemingway on the way Americans speak or on how writers everywhere write fiction.

Having found your right style you’ll be equipped to achieve the writer’s objective “to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader” (Hemingway). Everything with brevity, economy, simplicity, intensity. It isn’t possible to overstate the influence of Hemingway on the way Americans speak or on how writers everywhere write fiction.

© 2016 David J. Rogers

For my interview from the international teleconference with Ben Dean about Fighting to Win, click on the following link:

Order Fighting to Win: Samurai Techniques for Your Work and Life eBook by David J. Rogers

or

Order Waging Business Warfare: Lessons From the Military Masters in Achieving Competitive Superiority

or

I like the tips you have given for simplicity and clarity, but I am no fan of Hemingway. I studied his works in college, and the stories of course are strong, but I find the “perfect” sentences unsatisfying. Perhaps it is a gender thing. And in the example given from A Farewell to Arms, the last sentence runs on and says “and” seven times. Someone will have to explain to me the perfection in it.

LikeLike

Hemingway is my favorite writer, and I’ve learned from him. My great uncle was his best friend in high school here in the Chicago area, and Hemingway once said my uncle was the better writer. I asked my uncle about that, and he said, “I don’t know; Ernie was damn good.”

Yes, the “and” jag he gets into from time to time is annoying, though critics say it adds a lyricism to his writing. But I don’t agree. He got that from his friend Gertrude Stein’s theory of repetition. But he got over it later in his career, and I forgive him.

I think it is a gender thing to a good extent. Many women–my wife among them–can’t stand him. She doesn’t permit me to talk about him for more than one minute before she says, “I don’t like Hemingway.”

But he has an awful lot of valuable things to say about writing.

I’m happy you like the tips. I think they can benefit many writers.

Thank you for letting me know what you’re thinking. I enjoyed reading your comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think your tips are excellent, and very well ordered. Amusingly I was never a huge fan of Hemingway and you may be affected in your view by the family connection but he certainly got a seat at the top table. I am a big ( in American Literature terms ) fan of F. Scott-Fitzgerald. When you think The Great Gatsby is only about 55,000 words long but written so lucidly and with so many points of interest, not forgetting the gripping plot, I think he might well be at the top table as well, regardless of how he might get on with Hemingway.

I do enjoy your blog but I’m beginning to feel sorry for you and wonder if I should keep leaving these long-winded and over exhaustive comments !

LikeLike

Peter, I like Fitzgerald too, but not as much as I admire Hemingway’s work. You probably know they were very good friends. Fitzgerald discovered Hemingway when he–Fitzgerald–was famous and Hemingway was just starting his writing career.Fitzgerald helped Hemingway get published. They both had the same editor at Scribner’s–a publisher who published a book of mine.

I look forward to your comments. They’re not long-winded or over exhaustive. You always have something interesting to say.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not entirely friends although things started off well as I’m sure you know.

As Scott Donaldson said in a book reviewed by the New York Times, “Hemingway, who ”could ill abide being beholden to anyone,” clearly resented Fitzgerald’s help. He emerges from these pages as an ingrate and bully, a megalomaniac who projected his own insecurities onto those closest to him and who believed he needed to reject friends and lovers before they could reject him. Fitzgerald, in contrast, comes across as a well-meaning but annoying fellow who hero-worshiped the wrong people, and who consistently sabotaged himself by getting drunk and behaving like a fool.” and again, ”

Hemingway was condescending about Fitzgerald’s work and mocked his former friend as a coward, a lap dog to the rich and a henpecked husband in thrall to a manipulative woman. He likened Fitzgerald to a dying butterfly, a glass-jawed boxer and an unguided missile crashing to earth on a ”very steep trajectory.”

After Fitzgerald’s death in 1940 at 44, Hemingway’s attacks accelerated, in large measure, Mr.Donaldson suggests, because of the posthumous revival of Fitzgerald’s reputation. During the last years of his life, Fitzgerald indulged in the occasional gibe against his former friend (”Ernest would always give a helping hand to a man on a ledge a little higher up,” he remarked), but for the most part he seems to have regarded the lost friendship with wistful regret. ”

In the light of their unsettling connection a level of pleasing anonymity in the struggling authors club may not be so unwelcome 🙂

LikeLike

Hemingway was a very unpleasant person but the most influential writing stylist of the twentieth century. Writers’ personalities or how they behave socially I keep separate from their writing and what I can learn from it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seems like a wise approach, especially in these circumstances !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very useful advice. Thank you. Hugs, Barbara

LikeLike

Barbara, thanks so much. I’m happy that you will find the information useful. Let’s stay in touch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would be just fine. Have a good evening. Hugs, Barbara

LikeLiked by 1 person

David, I’m usually a skimmer, but read your article all the way through. Your words gave me pause since I tend to gravitate toward big words and flowery prose. You’ve given me courage to simplify. Thank you! 🙂

LikeLike

Penelope, thanks very much for your comment. If you want to break a big word/flowery language habit, read Haiku (no flowery language at all). And read Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises for the style, if not for the content. Read them again and again.

LikeLike